20 Photos Of Bomb Shelters During The Cold War & Red Scare

By | December 4, 2020

A major feature of the Cold War was the looming threat of nuclear strikes and the ever-present sensation of doom that accompanied it. While schools ran "duck and cover" drills that sent students huddling beneath their desks (fairly ineffective if the bomb was actually close enough to do damage), many families tried to find more practical protection in the horrible event that a bomb was about to detonate nearby. The fallout shelter was all the rage during the '50s and '60s, and some of them were quite impressive. How reliable they would have been if put to the test remains a mystery (hopefully forever), but they do show us just how far humanity will go to feel safe in an increasingly unpredictable and dangerous world.

Take the above photo, an interior view of a 4,500-lb. steel underground radiation fallout shelter located in a family's backyard in New York. A shelter of this type would be expected to survive the blast and protect the family from the initial fallout but wouldn't have sustained them for long. Companies that popped up across the country, eager to profit from the public's fears in the decades following World War II, hosted large exhibitions where they showed off prefabricated shelters just like the one shown above. The short-term but highly profitable bomb shelter bubble burst just as soon as America's anxiety subsided, but some shelters found second lives as extra storage space or even living or sleeping accommodations.

The safest place to be in the event of a nuclear blast is, of course, underground. A family would not only survive the blast wave but also the heat and possibly even lower their exposure to radiation. Diagrams like the one shown above were used by companies to show people how they could fit a shelter into their already existing homes. While this shelter would certainly be safer from the blast than a prefabricated aboveground shelter, it still lacks the ability to sustain a family for an extended period of time. If the detonation was close enough, it's also likely that the family would still suffer major side effects from radiation. While the initial blast of Hiroshima killed over 100,000 people, many survivors began to die months and even years later due to radiation poisoning and cancer.

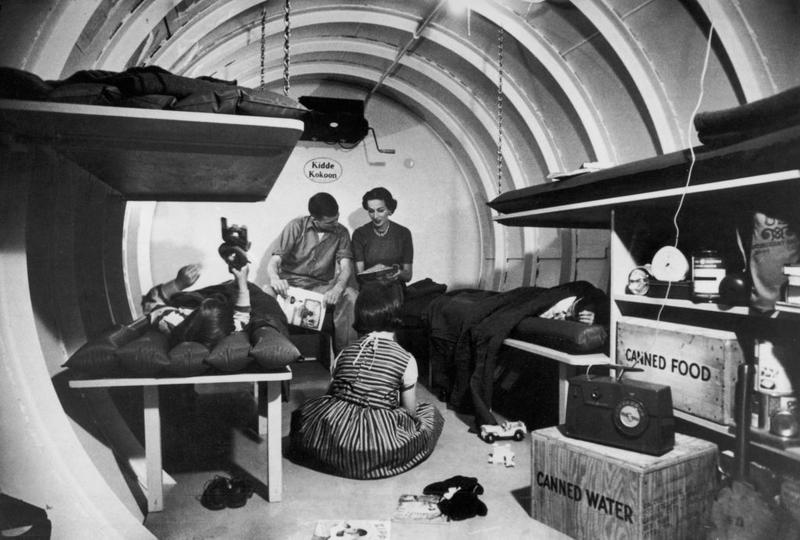

Seen at a shelter display exhibition in New York in 1961, this shelter was the next step up for a family looking for a longer-term solution to fallout. With more comfortable sleeping arrangements and canned food, this shelter has the potential to keep a family safe for weeks, which is all that's really necessary. While the initial burst of radiation from a bomb is beyond deadly, it dissipates with surprising speed.

The shelter-building craze was a boon for the construction industry, but it didn't rely solely on fearmongering. This Los Angeles pool-supply-company-turned-bunker-builder brought customers in with swimsuit-clad models who greeted them at the entrance in 1961. Fun fact: In 1946, the two-piece swimsuit was given its iconic name by designer Jaques Heim because he anticipated his design would be just as explosive as the recent Bikini Atoll nuclear bomb tests.

If there's one thing you need to survive in a shelter, it's food. Above is an exhibition example of the bare essentials, mostly canned goods and non-perishables, though dehydrated foods and powders like Tang were also popular items. Some families kept their shelters stocked up for decades, and companies like Campbell and Spam couldn't have been happier to provide.

This Los Angeles shelter, where model Mary Lou Miner posed for this photo in 1951, was available to the public, who would have been alerted by sirens placed throughout the city if a strike was imminent. Most city shelters could protect at most a few hundred people and were not usually designed to do anything more than protect citizens from the initial blast wave. In 1955, the Office of Civil Defense tested many building styles against actual nuclear blasts to determine their durability and found concrete and brick to be the most stable materials, granted they were at least a mile away from the explosion's center.

The Weedin Place shelter, built in Seattle, Washington in 1962, is a good example of a public shelter. It could protect over 100 people and served as a prototype for what they believed would be the wave of the future, but large public shelters just never seemed to take off in the U.S. like they did in other countries. The cost was high, and the Office of Civil Defense was never very confident that they would actually work well enough to be of value. The government did, however, invest millions of dollars into anti-missile and missile defense technology to track and shoot down any warheads that came their way.

In order to see just how useful their new shelters were, some families locked themselves inside for days. One common issue that arose during these tests was the necessity of at least one person being awake at all times to operate the manual air crank that supplied the shelter with oxygen. Families also found that cooking in the shelter made the space sweltering hot and decreased air quality. In shelters without plumbing, chemical toilets were used but were by no means a perfect solution. No one ever said survival was pretty.

This image of a remarkably well-kept mid-century bomb shelter located beneath a house in Woodland Hills, California shows the effort some families put into making their shelters feel like comfortable and livable extensions of their home. Like many concrete bunkers, this shelter is only accessible from a large steel door built into the ground and sealed from the inside, and it was equipped with electricity, a well-stocked kitchen, and indoor plumbing. These sorts of bunkers were more secure but also more costly—the average American family in the 1950s couldn't afford such a tricked-out nuclear pad.

This fallout shelter, located in Pittsburgh, was built in 1961, cost an estimated $8,000 in today's money, and illustrates the inventive storage solutions many families devised. Most family shelters also came with radios, which would have been crucial in case of a blast but may have proven useless if affected by a large enough electromagnetic pulse, which can sometimes arise as a result of nuclear detonation and against which most radio stations were completely unprotected.

Why settle for a shelter, though, when you could have a whole house? This bomb shelter from 1961 is located, of course, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Built beneath 26 feet of earth and concrete, this home boasts five bedrooms, full baths, a kitchen, and even a pool! With enough food and air, a family could stay in this comfortable shelter indefinitely, but it comes at a price. This shelter was recently put on the market for staggering $18 million.

Of course, if you wanted true safety from a nuclear blast, you were better off with a large-scale bomb shelter like this one, located in the remote wilderness of Arizona. Built by the U.S. government, this bunker encompassed not only three floors of work and living space but also a silo containing a TITAN II missile, the largest intercontinental missile of its time. Not only were you safe, you had the power of the atomic bomb at your disposal. It was abandoned after the Cold War and eventually sold (sans missile) in 2017.

Some nuclear shelters are currently being repurposed, like this Cold War–era bunker, which was built inside of a cave in Sweden and is now used as a data center. That doesn't mean the Swedish are completely over their fears of nuclear war, however. In the last few years, they've actually pushed to build more modern nuclear fallout shelters as tensions rise between them and Russia. Despite being a historically peaceful nation, they still believe they are in enough danger to dedicate over $100 million to building over 500 shelters in the coming years.

This Swedish shelter, built in 1955, was intended to hold over 20,000 citizens in the case of a nuclear attack. Europe suffered many air raids during World War II and knew the devastation even conventional bombs can cause.

Bunkers aren't just for humans. In 1963, a dairy farm in Nebraska decided to build and test a shelter to protect their precious bovine from the deadliest weapon known to mankind. Their huge underground shelter had enough space for 15 people plus a herd of milk-producing cattle. As crazy as it sounds, things actually went pretty smoothly when they tested it for two weeks. In fact, the cows seemed to adapt better than the humans, who showed signs of distress and anxiety very early on and whose sleep patterns took longer to adjust.

Located two stories underground, this bunker was not intended for the public but for the Office of Civil Ordnance and other civil leaders. It served as a base of operations for the intelligence community and local military leaders, but it was abandoned several decades ago, apparently abruptly. Maps, files, and furniture were all left behind, and they didn't even bother packing up the equipment or food. Why they left their post in such a hurry and never returned is a mystery.

Most fallout shelter entrances are fairly nondescript, like this one located in Hawaii. Once the doors are flung open, you are met with either a steep set of stairs or a ladder descending several feet underground. They can also be used as storm shelters in the case of hurricanes or tornadoes.

Other shelters are as impressive as they are foreboding. Built on the naval base in Pearl Harbor, this bunker actually predates the atomic bomb by a number of years, as it was intended to be an air raid shelter.

Rural Civil Defense, a publication which taught readers how to protect themselves in rural environments, assured rural readers that their communities would not be targeted by nuclear attacks and "should have sufficient warning" of any kind of fallout coming in from neighboring cities. They emphasized the use of shelters and food storage, discouraging readers from embracing the "fatalistic view" that nothing could be done to protect oneself from the bomb.

The fallout shelter's heyday ended in the 1970s, when Cold War tensions shifted from nuclear to proxy wars. By the '80s, all but the most anxious had abandoned them entirely, but maybe we should have kept the practice up. The 2020 Doomsday Clock, a measurement device invented by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, moved from two minutes to 100 seconds until midnight, marking the most dangerous period of time since the invention of the clock in 1947.