Blazing The Oregon Trail

By | January 17, 2019

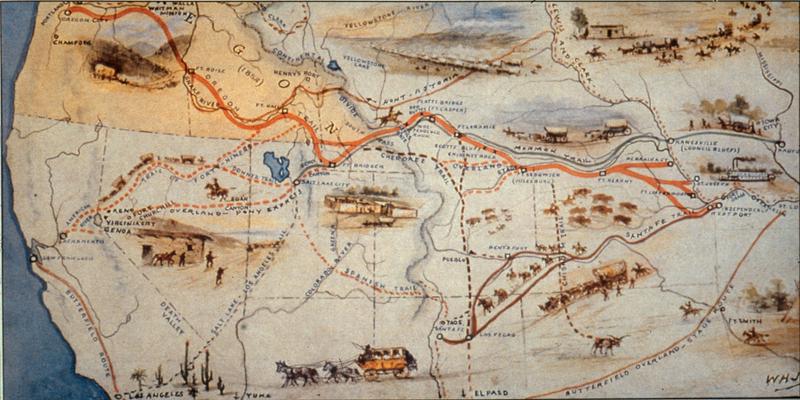

They traveled for a variety of reasons. Among those was the concept of Manifest Destiny, a sentiment that expansion was preordained. However, others were seeking financial stability or escape from the Civil War. The earliest travelers of the trail were trapper and fur traders who traveled on horseback or on foot. The Lewis and Clark Expedition from 1804 to 1806 was the government’s first attempt to explore the land to the west. In 1810, John Jacob Astor launched an expedition to Oregon, intent on opening a trading post for his American Fur Company. The expedition led to the discovery of a gap in the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming, which offered the easiest path across the Continental Divide and became known as the South Pass.

Once they set out on the journey, travelers were faced with many perils. Estimates of the number of people to perish along the way range from four to six percent, though some estimate as high as ten percent, of the total number of travelers. Most of these deaths were the result of accidents or disease. Typical accidents included falling under the wheels of a wagon, drowning, or even being accidentally shot. Prevalent diseases included dysentery, cholera, and smallpox. Some of these deaths were a result of simply running out of food and water. Conscientious travelers often left warnings for future passersby of nearby disease or contaminated water.

Offering temporary relief to the weary travelers were several outposts along the trail, which gave the Pioneers a chance to rest and restock their supplies. Among those outposts were Fort Kearny, Fort Laramie, Fort Walla (previously Marcus Whitman’s mission), and Fort Vancouver. In addition to outposts, there were also numerous landmarks to help travelers mark their progress. One of the most important of these was Independence Rock, which marked the halfway point of the journey. If travelers could reach it by July 4, they were on track to complete their journey before winter. Travelers often carved their names into the rock, leading it to become known as the “Great Register of the Desert.”

Eventually, the Oregon Trail was replaced by the transcontinental railroad as the most popular way to travel west, though by that time several towns had sprung up along the route. Between 1860 and 1888, it was used largely for cattle drives. While the full trail no longer exists, there are still remnants of it, including rock formations like Independence Rock which bear the names of the travelers, and areas where wagon ruts are still visible. In 1978, Congress established the Oregon National Historic Trail to preserve portions of the trail.