Flayed Lord Xipe Totec: An Ancient God Without Skin Dug Up In 2020

By | May 17, 2020

The first temple to the most metal of all the Aztec Gods, Xipe Totec A.K.A. Xipetotec and/or Our Lord The Flayed One, was discovered in 2019 during an excavation of Popoloca Indian ruins in the central state of Puebla. So who exactly is this god of life, death, rebirth, and agriculture? How did he get his incredibly awesome title? And why does he look so cool?

A Brief History Of The Flayed One

It might surprise you to learn that Xipe Totec is actually a central deity in Mesoamerican culture, especially for the Aztecs, and despite his tendency to wear the flayed skin of human sacrifices, he was considered the god of spring, renewal, and fertility. It's unclear exactly where this deity first appeared, but speculation has pointed back to the ancient Olmec God VI. Others argue that he first appeared in the Yope civilization, the people who inhabited the state of Guerrero from 650 to 1100 A.D. However, the first appearance of any art representing The Flayed One dates back to somewhere between the ninth and 12th century in the eastern shores of Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico.

Regardless of who first created him, The Flayed One became a major Aztec deity who was also worshiped by Maya, the Tlaxcaltecans, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, Tarascan, and Huastecs civilizations. Early mythology indicates Xipe Totec was the child of Ometeotl, a deity who was both male and female. The Aztecs took it a step further and said he was the brother of several of their most important gods, Tezcatlipoca, Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl.

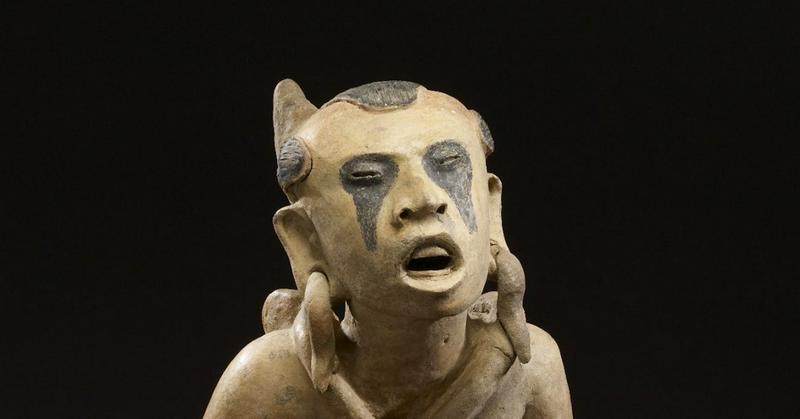

He was said to be "born of a ruddy color all over," earning him the nickname Red Tezcatlipoca, and he's usually portrayed wearing a suit of yellowed skin with patches of his own skin visible in places shown in red. Some of these depictions include intricate stitching over the chest of the skin suit, suggesting the spot where the sacrificial victim's heart was cut out before the flaying. Xipe Totec's hands emerged from the wrists of the skin suit, causing the skin's hands to dangle at the wrist. We must assume it was as gross as it was dope.

Much like his Aztec brothers, Xipe Totec was associated with death and diseases. However, he was thought to cure illnesses as well, especially visual afflictions like inflammation or even pink eye. The Aztecs also worshiped Totec as the god of new vegetation and a patron of metalworkers. Many believed the human skin Totec wore represented the "new skin" of spring vegetation covering the Earth.

Human Sacrifice: Now With More Flaying!

Aztecs believed that Xipe Totec carved off his flesh to provide food for humanity, symbolic of a snake shedding its skin or a maize seed shedding its outer layer prior to fertilization. The skinless version of Totec was depicted as a shimmering golden god, as he emerged newly reborn from his rotting, flayed skin after 20 days. The glowing god's skin was symbolic of the renewal of the seasons, as the old dirt and soil fertilized the new vegetation. He would then regrow his skin, only to once again slice it off and begin the process anew.

To celebrate their macabre god, Aztecs held an annual festival on the spring equinox called Tlacaxipehualiztli, which translates to "flaying of men." Forty days before the festival, the priests of Totec offered human sacrifices to appease the god, both for a good harvest and to cure villagers of diseases. These human sacrifices were often war captives or slaves who were taken from every ward of the city. Some of these human sacrifices dressed as Xipe Totec, adorned in feathers and gold jewelry, and walked around the village impersonating the deity for 40 days.

On the day of the festival, they were forced into a gladiatorial battle against the strongest and most fearless soldiers, which only ended when all the human sacrifices were dead. The "battle" was pretty one-sided, however, as the captives were bound to a stone platform before being made to "fight" these warriors. The captives were only given feathers to defend themselves against warriors armed with razor-sharp swords.

The following day, the priests wore the skins of those killed in the gladiator battle as they paraded around town, demanding praise and gifts from the villagers to show their love and reverence for the deity. Those who gave alms or gifts were blessed by Totec, either ensuring their harvest would be plentiful or perhaps to cure some eye-related ailment.

Another feature of the Tlacaxipehualiztli was the ritual sacrifice of captives. These unlucky (or incredibly honored, since their sacrifice would appease this most important deity) captives had their hearts cut out of their body before they were carefully flayed from head to toe so that their skin could be removed whole. The priests then wore the skin suits for 20 days after the sacrifice. Much like before, they were adorned with fancy jewelry and colorful feathers, which were gifts from the village. At the end of the 20-day fertility festival that followed the sacrifice, the flayed skins were removed from their wearers and placed inside containers with individual lids meant to stop the smell of decay from escaping, which were moved to a chamber underneath the temple.

The First Temple Of The Our Lord The Flayed One

One such temple was recently discovered by a team of archaeologists from the National Institute of Anthropology and History, led by Noemi Castillo Tejero. Initial excavations of the area revealed two altars with badly damaged sculptures of Xipe Totec, leading the team to believe there was more to be discovered. A while later, the team further excavated the site at Puebla state in south-central Mexico and confirmed their beliefs. They discovered two massive carved skulls, a statue's torso, and a small ceramic statue of the god that had an extra hand attached backward to one of the arms, suggesting the statue once depicted the god wearing a suit of flayed skin.

"Sculpturally, it is a very beautiful piece," said Tejero in a press release. "It is around 80 centimeters tall and has a hole in the stomach that was used, according to sources, to put in a green stone and 'bring them to life' for the ceremonies."

Tejero and her team confirmed that the layout of the newly discovered site, as well as the sculptures, matched with descriptions of the ancient ceremonies in documents from the Aztec period. Sometime between 1000 and 1260 A.D., the temple was built by the Popolocas (a Nahuatl term for various indigenous peoples of the area) at a complex known as Ndachjian-Tehuacan, which was later seized by the Aztecs.

This is the first temple to Xipe Totec discovered by archaeologists, who until then had only read about the existence of such places in documents from the Aztec period describing the Tlacaxipehualiztli ritual. However, it's still unclear to researchers if this temple was the same location where the rituals were performed. "If the Aztec sources could be relied upon, a singular temple to this deity (whatever his name is in Popoloca) does not necessarily indicate that this was the place of sacrifice," wrote University of Florida archaeologist Susan Gillespie. "The Aztec practice was to perform the sacrificial death in one or more places but to ritually store the skins in another after they had been worn by living humans for some days. So it could be that this is the temple where they were kept, making it all the more sacred."