The Granger Movement Of The 1860s

By | August 21, 2021

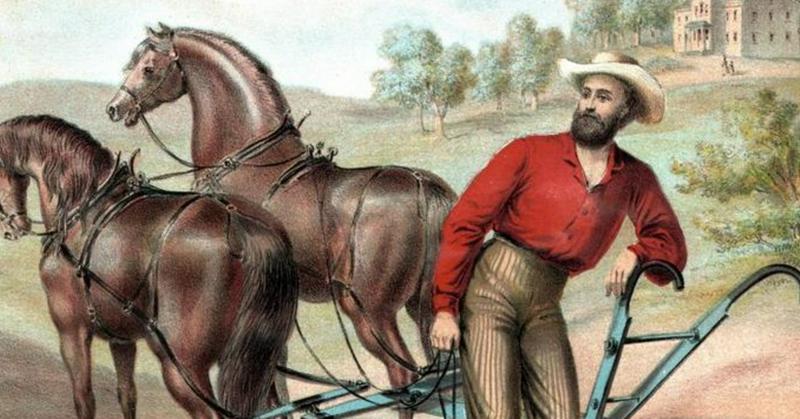

The Granger movement gave the nation's farmers a voice in federal government and reminded the general public of the importance of farming. Although not the original goal of the Patrons of Husbandry, better known as the Grange, this organization of farmers in the U.S. quickly discovered that they could leverage their unified power to push back against the railroads and grain elevators. And it all started with one man.

Oliver Hudson Kelley

Minnesota native Oliver Hudson Kelley had a reputation as a "book farmer." He read many books on agriculture, applied what he learned to his agricultural experiments, and never hesitated to implement new technology to improve his yields; according to legend, Kelley was the first person in the state to own a mechanical reaper.

In 1864, he was offered a position with the Department of Agriculture, which led to a tour of post–Civil War Southern farms two years later. What Kelley found dismayed him: There appeared to be no standardization of farming techniques across the region, which meant that not only was no one doing the same thing, no one was doing it right. As a member of the Masons, Kelley knew the advantages such a fraternal society can confer upon those seeking to share information, so he established the Patrons of Husbandry in 1867.

The Patrons Of Husbandry

Initially, the Patrons of Husbandry was founded merely to help the nation's farmers implement the most effective farming methods as well as address the social and economic needs of farm families, but the financial crisis of 1873 changed everything. The railroads farmers depended on to ship their crops to market began charging them more and more, as did the mills and grain elevators, which were often owned by the railroads. At the same time, Congress passed new legislation that reduced paper currency, increasing the need for gold or silver coins. For the nation's farmers, however, cash money was scarce.

As the agricultural community grew increasingly restless, the idea of banding together in a unified organization became more attractive. The Grange operated in only nine states at the beginning of the decade, but by the middle of the 1870s, every state in the Union had Grange organizations, who counted a whopping 800,000 farmers among their members. With such power in numbers and a clear cause of their growing unrest, the Grangers quickly shifted from a social and professional organization to a political one. They threw their considerable clout behind political parties and candidates who worked to pass laws to regulate the cost of transporting and storing grain and other crops.

Once the Grangers reckoned with their true power, they really went wild by building their own grain elevators, storage systems, and stores, which they established as cooperatives, to bypass the locomotive monopoly. These endeavors resulted in questionable success, but by cutting out the greedy middleman, the Grangers established an agricultural independence that is celebrated by farmers across the nation to this day.