1988: U.S. Supreme Court Defends Right To Satirize Public Figures

By | February 22, 2021

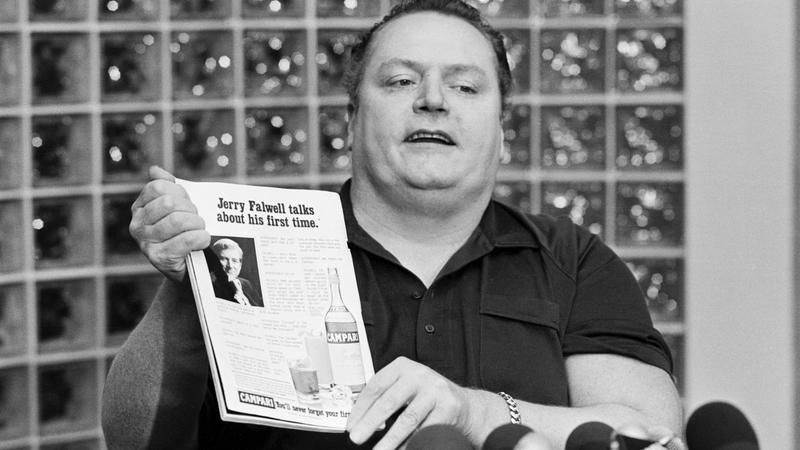

In 1988, the king of filth went head-to-head with the leader of the moral majority in the Supreme Court, battling over what could and couldn't be said about a public figure, in the infamous case of Hustler Magazine v. Falwell. It all started in 1983, when Larry Flynt ran a satirical ad for Campari in a 1983 issue of Hustler featuring fake quotes attributed to Jerry Falwell about losing his virginity in an incestuous encounter that took place in an outhouse. Flynt and Falwell spent the next five years in court, but in the end, the unlikely duo went from the worst of enemies to something like friends.

In The Red Corner: Jerry Falwell

On paper, Jerry Falwell was the polar opposite of Larry Flynt. Throughout the '60s, '70s, and '80s, he was one of the most well-known figures in evangelical Christianity and conservative politics, thanks to the monumental amount of air time he received after founding the Moral Majority, one of the largest political lobbying groups for evangelical Christians in the United States. He was largely responsible for leading evangelicals away from the Democratic Party following the election of Jimmy Carter and creating the modern Republican Party. Though he later welcomed debate on a variety of hot-button issues, the Jerry Falwell of the late 20th century was anything but open to a philosophical discussion of right and wrong, especially when it put him in the cross-hairs.

In The Blue Corner: Larry Flynt

To Jerry Falwell and his "moral majority," Larry Flynt was public enemy number one, the publisher of the raunchiest hardcore pornography magazine widely circulated in the U.S. Flynt was no stranger to the free speech struggle: In 1978, he was on a break at a misdemeanor obscenity trial when he was shot by a neo-Nazi serial killer, leaving him partially paralyzed for the rest of his life. It did little to slow him down: From his wheelchair, he continued publishing his magazine and fighting for his First Amendment right to do so.

Fight!

In the early '80s, Campari's print ads were all about someone's first time ... drinking Campari. They were filled with double entendres about "losing it" and "your first time," so Hustler writer Terry Abrahamson and art director Mike Salisbury decided a parody Campari ad was the perfect medium to skewer Jerry Falwell, whose prescriptive stance on society didn't sit well with the more sexually liberated. In the ad, "Falwell" describes his "first time" with his mother in an outhouse when they were both "drunk off our God-fearing asses on Campari," with no pretense of playing coy. Although the bottom of the page read "Ad parody—not to be taken seriously," Falwell didn't see the humor, sued Flynt for libel, and won $200,000 in damages.

Hustler Magazine V. Falwell

If Flynt hadn't been such an ardent defender of free speech, he would have taken his L. and gone home, but when the Fourth Circuit affirmed the lower court's ruling that the actual-malice standard of New York Times Company v. Sullivan applied in cases of intentional infliction of emotional distress where the plaintiff was a public figure, Flynt appealed to U.S. Supreme Court.

Flynt's dedication paid off. The Supreme Court voted unanimously to overturn the previous decisions and ruled that Hustler was protected by the First Amendment, not only saving Flynt $200,000 but establishing that public figures are prohibited from seeking damages for emotional distress if that distress was caused by a caricature, parody, or satire. The court's opinion read:

At the heart of the First Amendment is the recognition of the fundamental importance of the free flow of ideas and opinions on matters of public interest and concern. The freedom to speak one's mind is not only an aspect of individual liberty—and thus a good unto itself—but also is essential to the common quest for truth and the vitality of society as a whole. We have therefore been particularly vigilant to ensure that individual expressions of ideas remain free from governmentally imposed sanctions.

A decade later, Flynt and Falwell actually became friends after a fashion. Following the Hollywood film about Flynt's life and court battles, The People Vs. Larry Flynt, he and Falwell went on a roadshow of sorts to publicly debate philosophy, proving that the worst of ideological foes can come together in civil discourse, even after one fought the law to insult the other's mother.