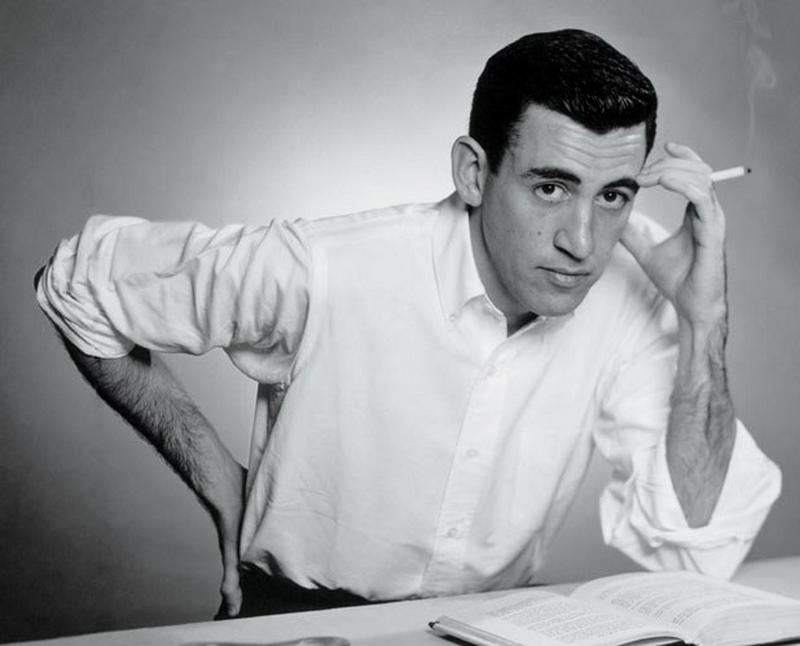

J.D. Salinger Was Basically Holden Caulfield

By | January 24, 2020

After publishing Catcher in the Rye, Salinger got out of town

J.D. Salinger wrote Catcher in the Rye in 1951 and then spent the rest of his life running away from its central character, Holden Caulfield. He didn't want to talk about the book, what it meant, or how it figured into his own similar upbringing. He even wrote short stories and novellas that tried to put the idea of J.D. Salinger as an angry young man to rest. He wanted the world to think he was a phony, just like everyone that Caulfield hated. The more Salinger tried to hide from his most popular creation, however, the clearer it became that he actually was the boy in the people-shooting hat wondering where the ducks go.

Salinger was born in Manhattan, and as a lifelong urbanite, he enjoyed the way the city moved, its cold winter streets, and the thrum of the crowd. After the publication of Catcher in the Rye, however, he went from anonymous Manhattanite to literary celebrity. In 1953, he came to the conclusion that contact with the public was a hindrance to his work, so on his birthday, he moved to a 90-acre rural compound in Cornish, New Hampshire. In doing so, he accomplished what Holden couldn't. He took the dough he made and lived the rest of his life in "a little cabin somewhere," free from "any g--damn stupid conversation with anybody."

His PTSD affected him for his entire adult life

Like Caulfield, Salinger suffered from a deep depression, but unlike the young boy, the author's mental distress came from his service during World War II. On D-Day, Salinger was a part of the second wave to storm Utah Beach, and while he managed to avoid the most heavily concentrated German defenses, he still witnessed some of the worst violence of his life.

As bad as the attack was, his most harrowing time during the war came when he was a part of a regiment meant to sweep the Hürtgen forest of German soldiers. The area was more heavily fortified than his commanding officers believed, and Salinger's friends and colleagues were killed by tree bursts and terrible weather alike. Almost half of the 2,517 casualties in the 12th Infantry died because of the elements.

Salinger carried the pain and depression that stemmed from his service throughout his entire life. On the pages of his work, violence and the military were portrayed as evil, while the innocent and conversations around the home were emblematic of ultimate good. It's likely that he spent much of the rest of his life trying to understand the horrors of World War II.

His early years in seclusion were spent playing with a Ouija board

You don't earn a reputation as a recluse without acting a little weird, and stories of Salinger's life after Rye are full of (unconfirmed) rumors of strange habits. People said he ate frozen peas for breakfast, saved his urine, and got deep into religion, but one oddity that has been reasonably verified was his predilection toward hanging out with teenagers. At 34, he tended to kick it with teens over soda pop and potato chips while going to baseball games and playing with a Ouija board that he referred to as "Pierce."

That ended after he gave an interview to a Vermont high school student in 1953. He got a little too comfortable and shared more about his private life than he usually did, probably assuming a school magazine had little reach and maybe also because he was possibly in a romantic relationship with the 16-year-old. After the girl's piece was published in the Claremont Daily Eagle, however, it was picked up for syndication across America. He stopped talking to the young reporter and started keeping friends who were quiet as he was, preferring to communicate by correspondence to his literary acquaintances. Biographer Shane Salerno told NPR:

J.D. Salinger was not a recluse; he was very private, and he wanted a private life. He was a man of deep, deep contradictions. He was a man who would write about renouncing the world and then write a letter to a friend about how much he liked the Whopper at Burger King.

He never stopped writing

The last official release from Salinger was 1965's "Hapworth 16, 1924," a short story that nevertheless took up nearly the entirety of the June 19, 1965 edition of The New Yorker. That's not to say he quit writing in 1965; on the contrary, the body of work he amassed over the next 40-plus years has attained almost mythical status. That's because, to the endless frustration of his fans, he refused to publish any of it. In 1974, he explained the joy he found in refusing to publish to The New York Times:

There is a marvelous peace in not publishing. It's peaceful. Still. Publishing is a terrible invasion of my privacy. I like to write. I love to write. But I write just for myself and my own pleasure.

After his death, there was talk of releasing pieces of his long-rumored work, but his son, Matt, deflected questions about this possibility by encouraging fans to appreciate the work they have:

I would love for more people to read his last two books, Franny and Zooey and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction, for I hear his voice the clearest in these. He loved writing and he loved his readers, and I hope his readers will be glad for an excuse to remember him in this way.

He protected his privacy by any means necessary

It wasn't all hanging out with teens and playing with Ouija boards in between writing volumes of unseen work. Much of Salinger's life after Rye was spent keeping people whom he viewed as trespassers out of his life, whether they were reporters, biographers, or nosy would-be writers. After he turned down British literary critic Ian Hamilton's offer to write his biography in 1984, Hamilton did it anyway, so two years later, Salinger took him to court to prevent the use of quotations and paraphrases from unpublished letters. After a series of appeals, the case went all the way to the Supreme Court. Salinger won the case, but in the process, he ended up letting more people into his private life than he wanted.

He was weird about relationships

While living as a "recluse," Salinger had an exceptional love life. He was known as quite the ladies' man throughout his 91 years, and Salinger certainly had a series of eyebrow-raising relationships. In 1955, he married 22-year-old Radcliffe student Claire Douglas and started a small family with the birth of his daughter in 1955 and his son in 1960. By 1966, however, Douglas had filed for divorce, claiming that carrying on their marriage "would seriously injure her health and endanger her reason."

In 1972, the author started dating a freshman from Yale, but they broke up after nearly a year. In the 1980s, he dated actress Elaine Joyce before marrying a 29-year-old nurse named Colleen O'Neill. This final relationship worked mostly because O'Neill was happy to live a quiet life with her husband.

Above all, Salinger wanted his work to speak for itself

Like Caulfield, Salinger spent his life searching for the good in the world. He wasn't perfect, but he was always striving for something. Far from unaware of what people thought of him, Salinger realized that people thought he was a weirdo hermit, but he hoped that people would gain a better understanding of his inner life from his work. As he told the New York Times in 1974, "I'm known as a strange, aloof kind of man, but all I'm doing is trying to protect myself and my work."