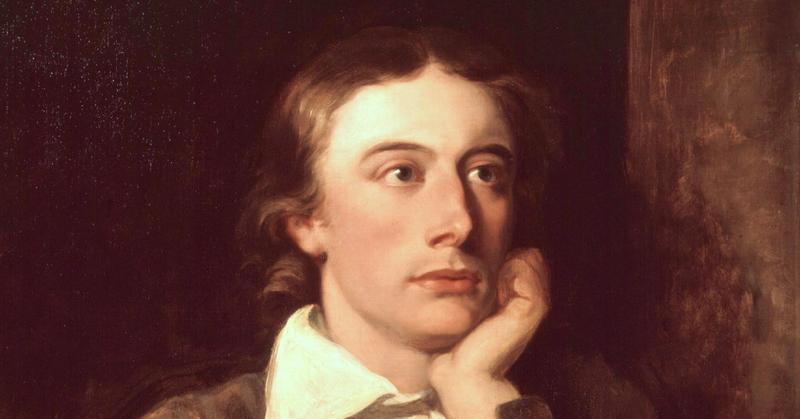

John Keats: Poet, Father Of Romanticism Who Peaked When He Was Young

By | March 29, 2021

During his life, John Keats was far from the most important poet of the Romantic movement. In fact, he had only been serious about poetry for six years, and the few volumes of his that were published earned deeply unfavorable reviews. At the time of his death in 1821 at age 25, he was certain that his work was destined to be forgotten. Thankfully, Keats was wrong.

Keats's Early Life

John Keats was born in London on October 31, 1795 into a romantic doom-and-gloom lifestyle. When he was eight years old, his father died after falling off a horse, and as the oldest of four children, Keats did his best to watch over his younger siblings when his mother died of tuberculosis six years later in 1810. Following his mother's death, Keats's maternal grandmother appointed two men, Richard Abbey and John Rowland Sandell, as the family's guardians.

Abbey briefly convinced Keats to pursue a career in medicine, apprenticing under an apothecary and surgeon at 15, but he preferred reading the classics and mythology. He found medicine far too gruesome for his disposition, and though he received his apothecary's license in 1816, he abandoned the medical profession shortly thereafter. Financially, it was a bad move, gore or no: He should have received £800 from his grandfather's trust when he turned 21, but likely due to Abbey's poor guardianship, he never saw it. Thanks to his mother, he had some money to split with his siblings, but it wasn't enough to afford him the privilege of lying around writing poetry all day.

The New Romantics

In 1816, Keats's sonnet "O Solitude" was published in The Examiner, boosting his confidence that this poetry thing might work out after all. He took off for the seaside town of Margate to write with his friend, Charles Cowden Clarke, and returned to London with the manuscript for Poems. The collection was a critical flop and an even worse financial disaster, but it earned Keats admission into the "new school of poetry" alongside Percy Shelley and John Hamilton Reynolds.

Today, Keats, Shelley, and Lord Byron are all lumped into one group as the Romantics, but at the time, Keats was a straggler within the group. Byron actually hated Keats's work as much as the critics, referring to it as "onanism" on paper. Shelley had a soft spot for the poet and tried to impart some wisdom unto his young friend, but Keats didn't listen. Rather than wait until he had a more substantial collection of poetry, as Shelley advised, Keats went forward with Endymion, a 4,000-line erotic romance based on a Greek myth written entirely in iambic pentameter that received the worst reviews of the young poet's career. The critical response was so harsh that Shelley considered publishing a favorable review out of sheer pity. Keats never recovered from the humiliation and almost gave up poetry entirely, but then he went to Wentworth Place.

Keats did most of his work at Wentworth Place

Fell In Love With A Girl

Keats wrote the most important work of his career during winter 1818–19, when he stayed at Wentworth Place following the traumatic illness and death of his brother, Tom, from tuberculosis. It was also the time and place that he met 18-year-old Fanny Brawne, who lived nearby.

Keats never cared much for women; he felt awkward around them but also displayed open disdain for them, once comparing them to "children to whom I would rather give a sugar plum than my time." Brawne was different. Describing her as "beautiful and elegant, graceful, silly, fashionable, and strange," he immediately fell in love, but he knew that his lack of prospects and declining health hardly made him a desirable beau. Though they were briefly engaged in the final months of his life, his love for Brawne went unrequited for years.

"Ode to a Nightingale," "The Autumn," and "The Eve of St Agnes," among other poems that have come to be known as some of the greatest works in the English language, were written during that winter at Wentworth, largely inspired by Brawne. In this verse from "Ode to a Nightingale," Keats's pain is clear:

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk

Death in Rome

Writ In Water

Tuberculosis was the Keats family disease. In early 1820, Keats suffered two lung hemorrhages, and after watching his brother die from the same illness, he knew what was to come. "I know the color of that blood!" he wrote to Charles Armitage Brown. "It is arterial blood. I cannot be deceived in that color. That drop of blood is my death warrant. I must die."

Keats moved to Italy with his friend, Joseph Severn, in September 1820 on the advice of his physicians to seek warmer weather, but their trip was a catastrophe. Upon arrival in Naples, the ship was held in quarantine for 10 days, destroying any chance of the more hospitable climate helping the doomed poet. Upon arrival at a villa on the Spanish Steps in Rome, now known as the Keats–Shelley Memorial House, Keats received questionable medical care. He was subjected to bloodletting and a diet of a single anchovy and slice of bread per day, intended to reduce the blood flow to his stomach, but despite or perhaps because of this treatment, he died on February 23, 1821.

With no money or family to bring Keats's body back to England, he was buried in Cemitero Acattolico, Rome's Protestant cemetery. His headstone bears no name, simply the inscription: "This grave contains all that was mortal of a young English poet who on his deathbed, in the bitterness of his heart at the malicious power of his enemies, desired these words to be engrave[d] on his tombstone: Here lies one whose name was writ in water." Shelley's ashes are also buried in the cemetery, and Severn is buried next to him. Today, Keats is considered one of the most important voices of the Romantic era. Would he be happy with his place in history? Would he even believe it? The answer is found in his most famous work, "Ode on a Grecian Urn," in which he wrote:

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on.