Martin Luther King, Jr.: Biography And Facts About The Civil Rights Movement's Greatest Orator

By | January 13, 2021

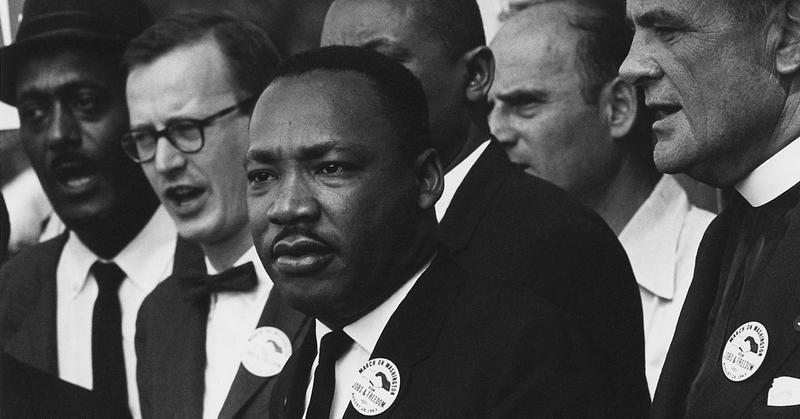

Whether you were alive when Martin Luther King, Jr. was marching for freedom as a Baptist minister and activist or you've just been inspired by his groundbreaking work, you should know that his life is much more than marching and giving speeches. His work to end segregation and racism earned him a Nobel Peace Prize and a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, but he was more than a collection of his accomplishments. Martin Luther King, Jr. was a man who who fought to be the face of desegregation while under intense scrutiny from both allies and enemies.

Not Always A Martin, But Always A King

Georgia plays an important role in King's life, not only because that's where he first became a known entity but because it's where he was born. On January 15, 1929, Michael King, Jr. came into the world via Atlanta, Georgia. His family was made up of ministers and sharecroppers, and his father was the head pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church from the early '30s.

Following a trip to the Europe, where King's father witnessed the rise of Nazism, he knew he had to denounce the fascist regime. He changed his and his son's names in honor of the German protestant leader upon his return to the States in 1934, though Martin Luther King, Jr.'s birth certificate wasn't changed until July 23, 1957.

Much of King's early life revolved around the scripture and violence. He read the Bible aloud daily and often found himself on the wrong end of his father's belt. According to his father, whenever he faced discipline, the young King stood still and quiet, taking the abuse without a word.

King was only a boy when he came face to face with brutal truth of racism. When he was six years old, he made friends with a young white boy, but when the two tried to play at the boy's house, the boy's parents forbid King from playing with their son. When King brought this up to his parents they explained racism to him as best as they could, and the young boy became determined to "hate every white person" until his parents explained that it was his Christian duty to love each and every human being, regardless of their beliefs.

The Young King

In his adolescence, King watched as his father fought segregation, and though he rarely overcame the structural racism of the South, he never stopped fighting for equal rights. In 1936, King, Sr. led a civil rights march to the city hall in Atlanta to protest voting rights discrimination, essentially providing a blueprint for how his son would spend his adult life. In high school, the younger King became known for his public speaking abilities, but after winning an oration contest in 1944, he was forced by a cruel bus driver to stand all the way to Georgia, leaving him scarred and frustrated. Rather than finish high school, King took the entry exam to Morehouse College as a junior and began attending at the age of 15.

While at Morehouse, King played football before deciding to study under minister Benjamin Mays, the man he referred to as his "spiritual mentor." In 1948, at the age of 19, King graduated from Morehouse with a B.A. in sociology before enrolling in the Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennsylvania, where he began to understand the importance of his public image. As a black minister, he knew he would be held to the highest moral standard and have to make tough choices, like breaking off his relationship with a German woman who worked at the school out of fear of the consequences of an interracial marriage.

After graduating from Crozer in 1951, King began his doctoral studies at Boston University while working as an assistant minister at Twelfth Baptist Church under the tutelage of a family friend. On June 18, 1953, King married Coretta Scott on her parent's lawn, but the young family never had a moment to enjoy their wedded bliss. By 1955, inspired by the arrest of Rosa Parks, King was leading his followers in a 385-day boycott of Montgomery's public transportation system, during which time his home was firebombed by a white supremacist. Standing feet away from the the charred remains of his former home, King told his supporters, "I want you to love our enemies. Be good to them, love them, and let them know you love them." Instantly, he became a star of the Civil Rights movement.

The same year, King earned his doctorate and began working as a pastor at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. In the 1980s, researchers discovered that King had plagiarized some of his dissertation, but after an investigation into the paper in 1991, there was no recommendation to revoke his degree.

Surveillance And Selma

King's star on the national stage led to new opportunities, both good and bad. In 1957, he began working with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a group dedicated to bringing together black churches across the South for nonviolent demonstrations for civil rights. The group soon found themselves under government surveillance, and in 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy warned King to distance himself from the S.C.L.C. and their alleged communist leanings.

To King, it hardly made a difference: He was already under the suspicion of F.B.I. Director J. Edgar Hoover, and nothing was going to change Hoover's insane desire to bring King down. Under the orders of the notorious director, who considered King a "subversive" and relentlessly sought to "neutralize" him, King's hotel rooms were bugged and his phone calls were monitored for evidence of communist, anarchist, or any other "-ist" leanings. When that didn't work, the F.B.I. shifted their focus to undermining King's moral position in the community, going so far as to send evidence of an extramarital affair to his wife along with a letter encouraging King to commit suicide to save his legacy.

Undeterred, King worked with the S.C.L.C. to organize mass marches and peaceful protest events that brought national attention to the myriad problems with the Jim Crow South, including the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous 17-minute "I Have a Dream" speech. A little over a year later, King and the S.C.L.C. found themselves in Selma, Alabama to register voters, where the months-long campaign came to a head after a local judge issued an injunction that made it illegal for more than three people affiliated with the S.C.L.C. or any of their offshoot Civil Rights groups to gather.

King defied the injunction on March 7, 1965, when he led 600 Civil Rights advocates in a march from Selma to the bridge into Montgomery, where they were met by the state police and local white supremacists. The police fired tear gas into the crowd of marchers and then beat them as they fell to the ground, choking on the fumes. The entire assault was captured on camera for the world to see, turning what was once a local clash into a national event. Federal troops were sent to assist with the march, and on March 21, the protesters once again walked to Selma, this time flanked by troops under strict orders to keep them safe. The horrific moment pushed the Voting Rights Act into law on August 6, 1965.

The Mountaintop

On March 29, 1968, King checked into Room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, where he was scheduled to address a rally of striking sanitation workers. In his final speech, King spoke prophetically about his own death:

And then I got to Memphis. And some began to say the threats, or talk about the threats that were out. What would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers? Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. So I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

The next day, April 4, 1968, King was shot by James Earl Ray at 6:01 P.M. as he stood on his motel's balcony and spoke with musician Ben Branch. Ray's bullet went through King's right cheek, pulverizing his jaw before ripping through his spine and lodging in his shoulder. King died just over an hour later at the age of 39.

While the assassination made headlines and King's mourning followers broke out into riots and cries of conspiracy, Ray booked it out of the country, but not for long. He was taken into custody two months later at Heathrow Airport while trying to leave London with a fake Canadian passport and admitted to the shooting on March 10, 1969 before recanting his confession less than a week later. He was sentenced to life in prison, where he died in 1998, having spent the rest of his time on Earth insisting he had nothing to do with King's murder.

If King's opponents hoped his assassination would bring the Civil Rights movement to a halt or that he would be forgotten, they were sorely mistaken. He was made a martyr by the Episcopal Church, and on November 2, 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a federal holiday to honor King, which was finally observed by all 50 states on January 17, 2000.