The History Of Miranda Rights: How The Supreme Court Passed This In The 1960s

By | June 11, 2020

If you're a fan of TV crime dramas, you probably have the Miranda Rights memorized. Anytime a suspect is taken into custody, the arresting officer(s) must inform them that they have the right to remain silent, anything they say can and will be used against them, etc. However, you won't find this script in the Bill of Rights or the original Constitution. In fact, it wasn't until June 13, 1966 that the United States Supreme Court ruled on Miranda v. Arizona, the court case that established the Miranda Rights.

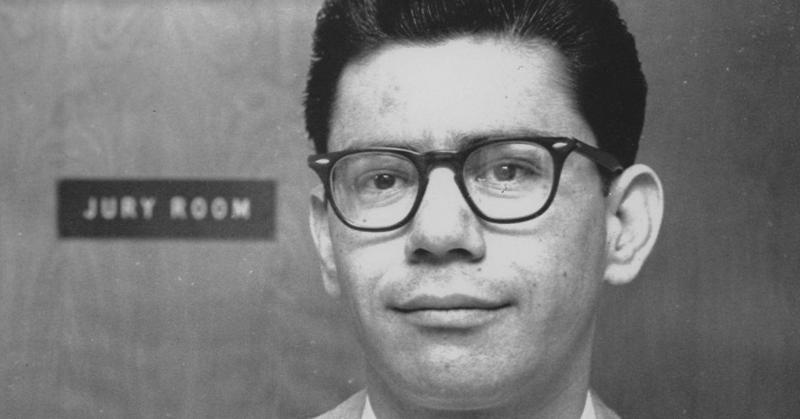

Ernesto Miranda

On March 2, 1963, a woman from Phoenix, Arizona reported to the police that she had been kidnapped, driven into the desert, raped, and released. She was given a lie detector test with inconclusive results, but she managed to provide police with a vehicle description and partial plate number. The information led police to Ernesto Miranda, a man with a prior conviction for voyeurism, who they subsequently took into custody and interrogated. A few hours later, they had a confession—for a while, at least.

Miranda's Rights

Based on that confession and a few shreds of circumstantial evidence, Ernesto Miranda was found guilty of the charges against him. The attorney that defended him never called him to testify during the trial, and the circumstances of the confession were not highlighted. As Miranda sat in the Arizona State Penitentiary, however, lawyers with the American Civil Liberties Union were taking a closer look at his case, particularly how the confession was obtained. It came to light that not only had none of the officers who interrogated Miranda informed him of his rights, the prosecuting attorney at the trial actually made it a point to tell the jury that Miranda never once asked for a lawyer. Of course, he didn't have any particular contempt for lawyers as a group or anything—he simply didn't know he had a right to one.

The Supreme Court

The ACLU filed an appeal on Miranda's behalf, taking the case all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled 5–4 in Miranda's favor on June 13, 1966. Chief Justice Earl Warren noted that the Fifth and Sixths Amendments to the U.S. Constitution guarantee a suspect the right to protection from self-incrimination and legal representation, neither of which were granted to Miranda during his interrogation.

Although these rights are clearly outlined by the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court found that many of the nation's police training manuals did not include any instruction to inform a suspect of their rights. The FBI's standard operating procedures did, so Warren took a literal page out of their book, quoting in his decision: "You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can, and will, be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford one, one will be appointed to you."

The Impact Of Miranda Rights

The ruling didn't mean Miranda was automatically set free, just that he got a shiny new trial, but the Supreme Court decision regarding Miranda's rights forever changed law enforcement procedures. Prior to the decision, the Fifth Amendment was only invoked in contempt of court cases, but requiring the recitation of the Miranda Rights upon arrest now protects both the suspect from violation of them and the arresting officer from accusations of such. It's a win-win, unless anyone involved is shady anyway.

Since the Miranda Rights were adopted by law enforcement agencies across the country, historians have tracked the impact of the Miranda Rights and found that the percentage of police-solved crimes decreased because arresting officers were getting fewer confessions. Statistics like these may appear grim as far as getting bad guys off the streets is concerned, but the general consensus is that the Miranda Rights have not inhibited law enforcement.

What Happened To Ernesto Miranda?

The case of the man whose name is forever attached to the police procedure of informing a suspect of his or her rights was sent back to Arizona for retrial in 1966, where he was found guilty a second time. He was released from jail in 1972, and just four years later, he got into an altercation over a card game at a bar. He was later stabbed to death in the men's bathroom. Though he met his end in the deepest, filthiest corners of obscurity, his legacy is anywhere but.