Ocoee Massacre Of 1920: When One Black Man Voting Sparked Over 30 Murders

By | November 5, 2020

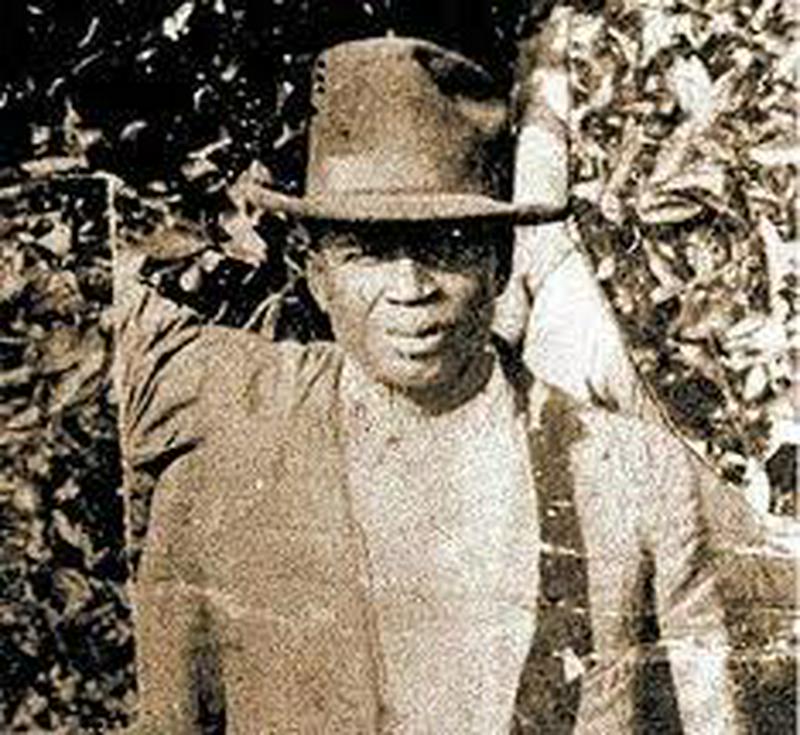

Incidents of Election Day violence have occurred for generations, but one of the most gruesome and demoralizing acts of it was the Ocoee massacre, where at least 50 black voters were murdered on November 2, 1920 in the small town in Orange County, Florida. Beginning with the lynching of Julius "July" Perry, a well-to-do businessman in the Ocoee area, the massacre spread across the county as the K.K.K. poured into Florida to destroy black-owned homes and businesses and kill anyone who got in their way. Many of the facts of this story were lost to time or never properly recorded in the first place, but what we do know exposes one of the most disheartening stories of modern American history.

Denied Their Rights

A day before the election in 1920, Klan members strolled through Southern streets wearing white robes, carrying crosses, and shouting through megaphones that any black residents who tried to vote would be sorry. Ocoee was no different. When Election Day came, many black voters found that their names were mysteriously missing from voter registration roles, while others were simply forced away from the polls.

Labor broker Moses Norman was initially turned away for not paying his $1 poll tax, and it's not clear if he went home to get a dollar or just left and came back. When he returned, he was in a car and ready to vote, but he was turned away once again. According to some versions of the story, he had a gun in his car, but others make no mention of it.

Ambushed At Home

From the moment the polls closed, the tenor of the day changed from an already grim mood to a bloodlust that destroyed the town as the white men from the polls armed themselves and drove off in search of Norman at the home of his friend, July Perry. Led by the West Point–trained Samuel T. Salisbury, the men barged into Perry's home, where Salisbury was greeted by Perry's teenage daughter, Coretha, and her shotgun in his belly. He pushed it away just as she squeezed the trigger, and the blast to his arm sent him to the ground as gunfire broke out. Salisbury, the former police chief of Orlando, later served two terms as mayor of Ocoee in the 1950s.

The firefight pushed the men outside and away from the home, but the Perry family knew that they'd return. Perry was injured, so he and his wife escaped into a sugar cane field while his sons hid in a barn and Coretha stayed in the house to take care of her wounds. The respite was brief. As fighting broke out in Ocoee proper, Perry was found in the field and dragged to the Orange County jail in Orlando. While he sat in his cell, awaiting his fate, the black neighborhoods of Ocoee burned. The white mob never caught up with Norman, possibly because it's believed that he left for New York City on the night of the Ocoee massacre.

The Lynching Of July Perry

Later that night, a white mob made their way into the jail, overpowered the officers on duty, and removed Perry from custody. They dragged him behind a car to the entrance of the Orlando Country Club near Lake Concord, where he was shot multiple times and strung up on a telephone pole. Perry was hanged in full view of the home of Judge John M. Cheney, a white man who had counseled Perry and Norman on their voting rights. Two months earlier, the K.K.K. sent a letter to Cheney, warning that his actions had "consequences."

The terror didn't end with the death of July Perry. The white mob grew larger with a call for local World War I vets to surround Ococee to prevent anyone from entering or escaping. Dynamite was thrown into the homes of black residents, fields were set on fire, and the black community was pretty much run out of town. Later that month, a celebratory dinner was thrown for the white ex-servicemen who participated in the massacre under the guise of restoring order to the town.

The Legacy Of The Ocoee Massacre

Eight months after the Ocoee massacre, grim reverberations of Perry's murder continued to echo throughout Florida. When Perry's brother-in-law, George Betsey, moved to the nearby town of Parramore, he was arrested by the Orlando police for bootlegging, but his real crime was spreading the word about the gruesome events of election night in Ocoee. Betsey was found the next day chained to a lamppost, painted with red and white stripes from the waist up and his head tied in a sack. He was lucky to be alive.

The message was received. Many black landowners who had lived in the Orange County area since 1880 dropped everything and left, and within a decade of the massacre, only two black residents remained in Ocoee. With no one in Ocoee to tell the truth about what happened on election night in 1920, it was left to white supremacists to fill in the gaps. The massacre was turned into a riot in the history books, blaming black residents for the violence of the evening, but Rachel Allen, director of the Peace and Justice Institute at Valencia College, summed up the reality of the situation:

The Black perception is it was a massacre, a violent attack on a prospering neighborhood. Whites from Orlando and Winter Garden, many with Klan ties, came with an intent to disrupt and intimidate and frankly terrorize Black leaders who had gained power and standing, and they did just that.