Policarpa: The Teenage Spy

By | June 27, 2021

Policarpa Salavarrieta, seamstress, spy, and heroine of Colombian independence, was born January 26, 1795 in the small town of Guaduas. Young Policarpa was entranced by thoughts of freedom from an early age, as both her brothers moonlighted as rebels for the independence of the Spanish-ruled Viceroyalty of New Granada (present-day Colombia). She was orphaned at the tender age of seven due to a horrific smallpox outbreak and forced to work as a seamstress to support herself.

At the time, New Granada was in flux, as many loyalists still supported the Spanish crown despite growing resentment of foreign taxes and denial of self-governance. (Sound familiar?) In 1808, Napoleon of France decided that one country wasn't enough for him and deposed King Ferdinand VII of Spain from his rule over not only his country but his many colonies. This left a vacuum of power that created the opportunity for many to form their own rebel governments. In Spain itself, the Supreme Central Junta announced itself as the true governance while Ferdinand was locked away in France.

Meanwhile, several other juntas formed across the Americas to create their own localized systems of power, spurred on by the still-lingering dreams of freedom from the Comunero Rebellion. At only age 15, Policarpa began keeping tabs on those she sewed and tailored clothes for, passing on the plans of wealthy Spanish loyalists to the ears of local rebel groups. The small, quiet, and seemingly timid girl often went overlooked and unnoticed, making her a uniquely effective spy. She even got away with stealing loyalists' letters from the very houses she worked in.

In 1817, Policarpa took a leap of revolutionary faith, hopping over to the larger city of Bogota to infiltrate the ranks of even more influential loyalists. She arrived in the city with letters from revolutionary leaders like Ambrosio Almeyda to gain favor with local spy ringleader Andrea Ricaurte, living in her home while continuing her sewing spy work. She sneaked food to prisoners, made uniforms for guerrilla fighters, and even ran weapons to rebel forces.

Her run of good luck came to an end when Alejo Sabarain, revolutionary guerrilla fighter and possible lover of then-20-year-old Policarpa, was arrested for espionage and found with letters implicating her in the spy ring. Ferdinand had retaken the throne of Spain in 1814, so he was pretty adamant about eradicating any threats of independence within his colonies and sent his soldiers to relay the ultimate punishment to any found guilty of treason against the crown.

When the police came knocking on Ricaurte's door, Policarpa made one final contribution to the cause by burning all documentation that may have implicated anyone else in the home, thereby saving the rest of the spy ring, before turning herself over to the Spanish authorities. She was taken to the makeshift prison at Universidad del Rosario, an ominous symbol of the country's direction, and sentenced to death by firing squad. As she was ushered into the courtyard alongside Sabarain and five others before a crowd on November 14, 1817, Policarpa shouted out the cause for independence one last time:

Indolent people! How different would your fate be today if you knew the price of freedom? But it is not too late. See that, though young and a woman, I have more than enough courage to suffer this death and a thousand more. Do not forget my example.

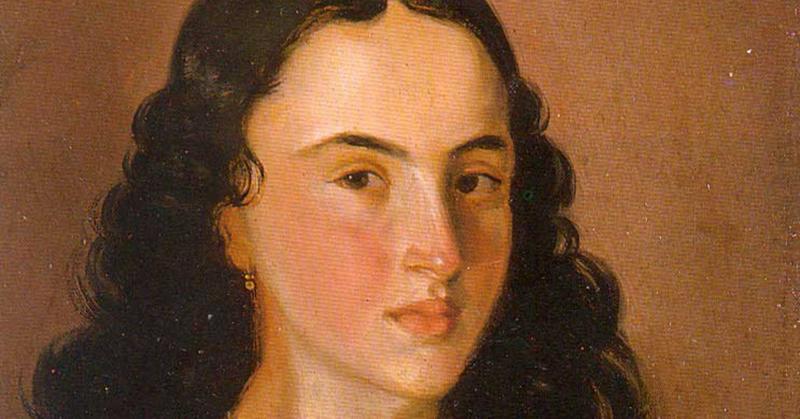

Killing the rebels did not have the desired effect on the crowd, and revolutionary fervor only grew stronger as many began to view the young spies as martyrs for the cause of freedom. Plays were written about Policarpa's life, and when Spanish forces were at last banished from the region in 1823, the newly formed Colombia commemorated her by not only celebrating the annual Day of the Woman on the date of Policarpa's death but also adding her portrait to the 10,000-pesos bill. She is seen as the face of courage, strength, and Colombian pride to this day.