Rarely Seen Photos Of Real Americans

By | May 12, 2020

Who would you consider to be the REAL Americans? Beware, when we get into this kind of discussion there are many mix views. But there's one thing we can all agree on, the collection of photographs in this gallery are rarely seen and truly for mature audiences only.

Some of the stories and photos are hard to look at and some are terrifying...try not to gasp. Have no fear, it's time to journey into the mysterious past, and lose ourselves in the imagination of what life was really like back when these images were captured.

Warning, some people may be triggered by the idea of who the REAL Americans really are...so pay attention to the stories each photograph tells and when you get to the end of the gallery you can make up your own mind. Onward!

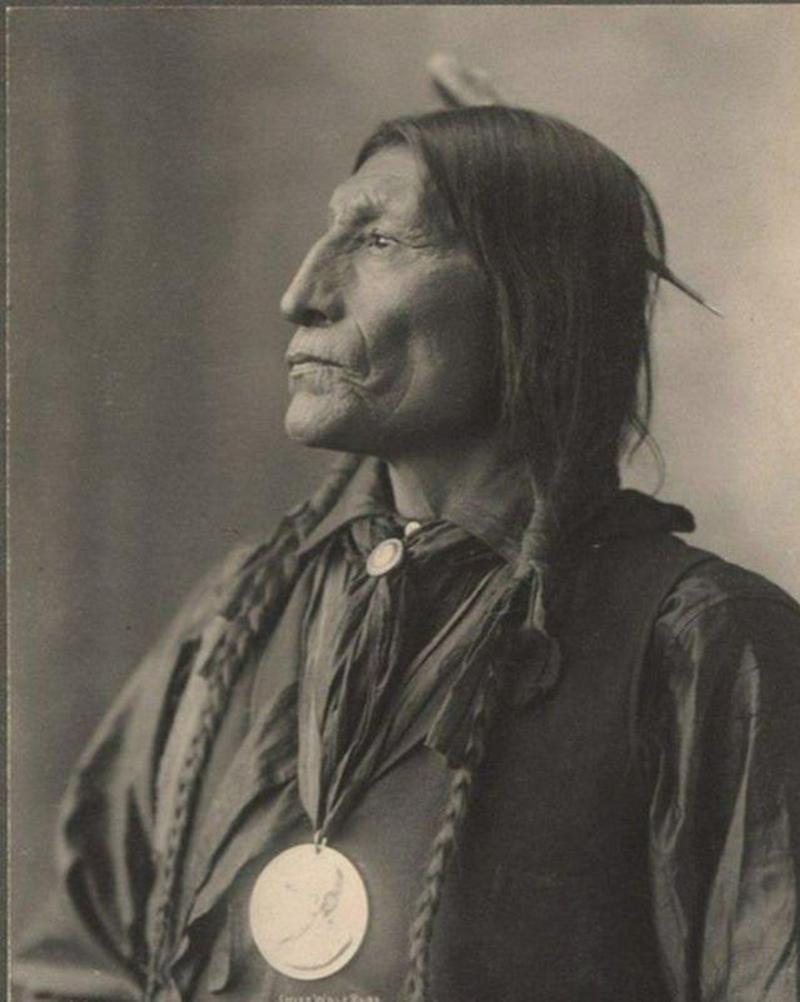

As a leader of the southern Cheyenne Indian tribe, Wolf Robe earned the Benjamin Harrison Peace Medal in 1890 for his assistance in the Cherokee Commission, a three-person bi-partisan committee that worked to legally acquire land occupied by the Cherokee Nation and other tribes in the Oklahoma Territory in order for use with non-indigenous people.

Wolf Robe is one of the most well respected members of the Cheyenne Nation not only for his grace under pressure but for the way he insured that his people would forgo their useless slaughter at the hands of the U.S. government.

A favorite of photographers like F.A. Rinehart and Nancy DeGill, it’s believed that his likeness was used for the profile on the “Indian Head Nickel.”

This is Joe Medicine Crow (1913 - 2016) who was a war chief and historian of the Crow Nation

Joe Medicine Crow spent World War 2 fighting the Nazis while carrying out the four must-dos to become a war chief. While going into battle he wore his war paint - two red stripes on his arms and a sacred yellow painted eagle feather under his helmet.

During his time in U.S. Army Joe became a war chief after he accomplished the following four tasks:

- Touching an enemy without killing him

- Taking an enemy's weapon

- Leading a war party

- Stealing an enemy's horse

The first two goals were carried out after he disarmed a German soldier and knocked the rifle from his hands. The two then took part in hand to hand combat that Jim broke off shortly before killing the soldier.

Following this feat, Joe lead a group of seven soldiers along with a pack of explosives through German territory. On top of that he stole 50 horses from a Nazi camp, singing a native song as he rode corralled them back to the Army camp.

In 2009, Jim was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. In 2016 he passed away at the age of 102.

Taken in 1913, this photo shows members of the Blackfoot, a highly nomadic tribe who initially lived in the Great Lakes before spreading out to take over land that stretched form current day Edmonton, Alberta to Yellowstone, and South Dakota to what we now refer to as Glacier National Park.

Their hold over the land came to an untimely end when European and American travelers ceded lands from the Blackfeet in the 19th century.

In 1895 Chief White Calf authorized the sale of an area that held Chief Mountain and the region in the southeast at Two Medicine, about 800,000 acres, for $1.5 million along with the promise that the Blackfeet would be able to maintain hunting rights on the land.

It may seem strange that Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill formed a partnership in the 19th century, after all Sitting Bull was a leader of the Lakota leader who lead his people in a resistance against the United States government.

He worked as a performer with Buffalo Bill's Wild West show for four months in 1885. During his portion of the show he made $50 a day (about $1,423 today) to ride around the arena and he allegedly cursed the audience in Lakota - although this is a rumor. Even though he left the show the two men formed a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives.

After working with Buffalo Bill, Sitting Bull returned to South Dakota where he fought support the Ghost Dance movement. During a battle in 1890 with the U.S. government at Fort Yates Sitting Bull was shot in the side and head. He was taken to nearby Fort Yates for burial.

When Laton Alton Huffman captured this photo of Pretty Nose in the late 19th century he had no idea that he was showing future generations the equality that existed in Native American tribes.

Pretty Nose was a war chief with the Arapaho tribe and even fought at the Battle of Little Bighorn. She’s often referred to as belonging to the Cheyenne tribe, but researchers have identified her as Arapaho based on her red, black, and white beaded cuffs.

She survived well into the 1950s, so long that she saw her grandson, Mark Soldier Wolf, become an Arapaho tribal elder, go off to serve in Korea with the Marine Corps, and return home safely.

Low Dog was one of the fighting chiefs of the Sioux at the Battle of Little Big Horn. 1870s

Fighting alongside Sitting Bull at the Battle of Little Big Horn, Low Dog was witness to some of the most intense warfare that the Lakota had ever seen. After becoming a war chief at the young age of 14, he had to go to battle with the U.S. military, something that must have been daunting in spite of his bravery.

Following the end of Little Bighorn, Low Dog gave an account of his reasoning for going into battle, stating that he refused to be told what to do by any man regardless of his color. He explained:

When it began to be plain that we would have to yield or fight, we had a great many councils. I said, why should I be kept as an humble man, when I am a brave warrior and on my own lands? The game is mine, and the hills, and the valleys, and the white man has no right to say where I shall go or what I shall do. If any white man tries to destroy my property, or take my lands, I will take my gun, get on my horse, and go punish him.

Best known as an Apache leader who was quick to shut down anyone trying to get in his way, Geronimo kept Mexican and American forces from pushing his people from their tribal lands.

In his final grapple with the U.S. military a quarter of the army was focused on pushing him off of tribal lands, they finally succeeded on September 4, 1886 and spent the last 20 years of his life as a prisoner of war.

Even as a prisoner of the U.S. military Geronimo got out and about. This photo was taken at the the Miller brothers’ 101 Ranch, located southwest of Ponca City, Oklahoma, where Geronimo was attending with a group of soldiers. The Locomobile Model C belonged to Edward Le Clair Sr., a Ponca Indian who was happy to take Geronimo for a spin.

From 1785 to 1922, White Wolf, was supposedly the oldest Native American to have ever lived at 137 years of age.

Chief John Smith, also known as White Wolf and Gaa-binagwiiyaas or “When The Flesh Peels Off” was on this Earth for an incredibly long time, so long that it’s not entirely clear how old he was. At his youngest he was 100 years old, but it’s believed that he was decades older than that.

Aside from his incredible age, Smith was one of the most photographed Native Americans of his time. C.N. Christensen of Cass Lake, Minnesota used Smith as a model for numerous cabinet photos, giving Smith fame that allowed him to travel through the midwest selling his own photos and riding the rails for free.

Smith was a Chippewa Indian who spent much of his time in Minnesota where he took on at least eight wives and had one adopted son. He passed away in 1922 and was buried in the Pine Grove Cemetery in Cass Lake.

Known alternatively as Gertrude Simmons, or Red Bird, Zitkala-Sa was a Native American activist who spent her adult life championing the indigenous way of life while fighting to expand the opportunities of her people and protecting her culture.

After studying at Earlham College, a Quaker school in Indiana, she taught at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, while publishing autobiographical essays in The Atlantic and Harper’s Monthly.

In 1902 she married Raymond Talesfase Bonnin and moved to a reservation in Utah where she collaborated with the composer William F. Hanson, writing the libretto for the opera The Sun Dance before becoming the secretary of the Society of the American Indian.

She and her husband moved to Washington, D.C., where she served as a liaison between the society and the Bureau of Indian Affairs before creating the National Council of American Indians in 1926. Even as her life came to a close in 1938 she continued working for the advancement of the Native American people.

Jim Thorpe (1887 - 1953) was a Native American athlete from Oklahoma and an Olympic gold medalist

It’s an understatement to say this but it’s not easy to win an Olympic medal (or even get to the Olympics) but Jim Thorpe managed to do both with a pair of mismatched shoes. To backtrack, Thorpe won his spot on the Olympic track team with a normal pair of sneakers but when he arrived for the track and field competition at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, someone walked off with his shoes.

This didn’t deter Thornton. A teammate lent him one shoe and he found another in the garbage, unfortunately it was too big. To solve that problem he wore extra socks. Today, Olympic runners would have shoe companies throwing merch at them, but in 1912 Thorpe just had to make do - he won two gold medals that day.

Throughout the games that year the only event that Thorpe didn’t win was the javelin throw - he’d never tried it before. Even so, he finished with a bronze medal.

Seated close to the evening fire, old man Gray Mountain, 91, told his small grandchildren legends about the early days of the Navajo people.⠀

One of the most important aspects of the Navajo culture is their storytelling. Like many indigenous cultures, providing an oral history not only continues to develop a rich heritage but it reminds young people of the lineage within their families.

Laura Tohe, an associate professor of English at ASU, and a member of the Navajo people grew up around storytellers and says that this kind of handing down of the traditions is an important way of life for their tribe. She explains:

Storytelling is part of the oral tradition of indigenous peoples. Stories impart values, language, memories, ethics and philosophy, passing them to the next generation. A lot of people think of storytelling as just entertainment for kids, but for the Diné it helps maintain tradition and language.

Born Sinté Máza, of the Oglala Lakota Nation, Chief Iron Tail grew up to lead a Lakota tribe and even played a part in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show in the 1800s. Major Israel McCreight, a 19th century expert on American Indian culture described Iron Tail as:

Not a war chief…but a wise counselor and diplomat, always dignified, quiet and never given to boasting… He always had a smile and was fond of children, horses and friends.

When Iron Tail performed with the Wild West Show as many as 12,000 people saw him perform each day and he continued working with Wild Bill until 1913.

A Ute warrior and his dog in the Eastern slope of the Wasatch Mountains, Utah, 1873

If you pass through Colorado you’ll find yourself in Ute country. The Ute tribe were some of the oldest inhabitants of the Southwest, specifically taking up land in Utah and Colorado where they hunted and planted crops. In the 17 century they began trading with the Spanish and began using horses that they earned in those trades to spread out their tribe and hunt larger game.

Life for the Utes became a daily stress when Mormons moved to the region, followed shortly by gold hungry settlers in the summer of 1858. Prospectors and settlers forced the Ute from Utah, a land which drew its name from the tribe.

In 1874 the Utes signed the Brunot Treaty, a document which the tribe believes surreptitiously took their land away from them. Today the Utes live on reservations throughout the Southwest, making money from casinos throughout Colorado.

In the Sioux language Oglala Sioux means, “to scatter one’s own.” The Oglala Sioux along with the six other groups making up the Lakota were one of the largest tribes in America in the 17th and 18th centuries, but by the 1800s the groups were separated.

In the 1820s and ‘30s the Oglala joined together with four other sects of the Sioux to create the “Sioux Alliance.” This group went to war with the Western Sioux yo gain more farming and hunting land.

By the late 1800s the Sioux Alliance was heavily fractured, with the Kiyuksa, the Oyuhpe and the True Oglala polarizing themselves into smaller and smaller groups due to the stress of the American government moving in on their territory.

Lee Pickett’s photography of the Native people who populated the Pacific Northwest, specifically in Snohomish, King and Chelan Counties in Washington State provide a keen insight into a group of people who are often left out of the conversation when we speak about Native Americans.

This photo of a 114 year old woman not only shows the resilience of America’s native people, but the way that the indigenous lifestyle of communing with the land fostered long life and good health.

It’s not clear which tribe Mahalia was a part of, but it’s most likely that she was in the Suquamish, Duwamish, Nisqually, Snoqualmie, or Muckleshoot.

Native American couple, Situwuka and Katkwachsnea, 1912

Not much is known about Situwuka and Katkwachsnea, although the date of this photo offers some insight into what their lives were like at the time. Most Native Americans in the early years of the 20th century had been forced to vacate their ancestral land for reservations.

By the 1890s the U.S. government "allotment" program began winnowing down Native lands from 138 million acres in 1887 to its eventual size of 48 million acres by 1934.

This couple was likely living on a government reservation, probably mixing with tribes and people that they didn’t know. They were turned into vagabonds in their own country.

This Hupa man gazing into a stream, waiting to catch a meal for his family or maybe even his tribe was captured on photograph by Edward Curtis, a photographer famous for his work with people of the American west.

Snapped in 1923, this shot was taken at the “Sugar Bowl” an area in Nevada county in the Northwestern part of California. Much of their diet consisted of salmon, which is probably what this fellow was fishing for.

The Hupa were a kind of amalgam of natives of the Pacific Northwest and California, and more often than not they lived on riverbanks with semi-subterranean buildings when men slept and took sweat baths.

The photo of this skinny Navajo silversmith was taken by Ben Wittick, the photographer who snapped the only known and surviving photo of Billy the Kid. Not all of Wittick’s photos were of world famous outlaws, many of the photos that he captured told stories of the American southwest, they gave insight into Native life, and the people who sought their fortunes in the west.

The Navajo people began plying the trade of silversmithing in the 19th century, prior to that the tribe acquired the few Silver ornaments they owned through trade with Hispanic settlers and neighboring tribes on the plains.

In 1865 a Navajo silversmith known as Atsidi Sani introduced silversmithing to the Navajo people, and its likely he who taught Slim how to create such beautiful pieces of jewelry.

Photograph of “Rabbit Tail,” who was a member of the Shoshone tribe and worked as a U.S. Army scout. (1895)

Known as the “grass house people,” the Shoshone traditionally lived in a variety of areas from Wyoming to Idaho, Nevada, and Utah - some members of the tribe migrated east to Texas where they took on the name “Comanche” by the 1700s.

In the 1860s the Shoshone fought against the U.S. military in the Snake War and the Bannock War, but in 187 they joined up with the U.S. army to take action against the Lakota and Cheyenne.

It’s most likely that Rabbit-Tail was working with the U.S. military in the Battle of the Rosebud, a long and bloody engagement that was a set up for the Battle of Little Bighorn and that ended with no real victor in spite of American forces claiming the day.

Beautiful girl with her pet

That may look like a wolf cub, but it’s most likely what’s known as a “Native American Dog,” a breed similar to the Canadian Eskimo Dog. They look like a little like huskies, but also share traits with Alaskan Malamutes, Greenland Dogs, and even chihuahuas.

These early dogs descended from Eurasian Grey Wolves which were brought to the Americas by people migrating across the Beringian Land Bridge, although it’s likely that over the course of 9,000 years at least four different dog types were introduced.

The Native American dogs look and sound like wolves and while they were definitely used for sledding and as watch dogs they were also bred for companionship.

Portrait of Kaw-U-Tz of the Caddo Nation, 1906

Expanding throughout East Texas, Louisiana, and parts of Arkansas and Oklahoma, the Caddo Nation were a tribe of farmers doing their best in an unkind part of the country. They made their way through the pine trees and humid marsh lands where they raised corn, beans, and squash.

More often than not the Caddo lived in grass huts which were shaped into tall cone like structures. Scholars believe that they made such good friends with the Spanish because the explorers liked how they furnished their homes.

Aside from growing vegetables, the Caddo used the local pine trees to create bows and arrows that were used whenever they went to war with neighboring enemy tribes.

This starkly beautiful photo of a Native man shows Bear’s Belly, a member of the Arikara who was born in 1847 in what we now know as North Dakota. Bear’s Belly was one of the most respected warriors of the tribe, he gained his famous bear skin during battle in which he brought down three bears at once.

In 1909 this brave warrior was photographed by Edward Curtis, a photographer and ethnologist who focused on the American West, during a series of sessions that J.P. Morgan funded to the tune of $75,000.

Curtis's plan was not just to photograph the Native people but to document as much their traditional life as he could before their way of life vanished.

A Navajo man in ceremonial dress as Nayenezgani, a Navajo deity, 1903

The Navajo people had a series of deities whom they held in high regards but none of them were as cool as Nayenezgani, literally the “slayer of alien gods.” It’s believed that Nayenezgani protected the Navajo people from evil spirits who walked the Earth, killing and eating lonesome travelers.

According to Navajo mythology Nayenzgani works with his twin brother Tobadzischini to destroy monsters, turning them to stone and making up the large rock formations known as Monument Valley in Arizona.

The Navajo people still wear masks depicting the monster slayers today on ceremonies in honor of this fascinating story.

Photographer William E. Irwin worked in Oklahoma, New Mexico and Arizona throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries where he took numerous photos of southwestern Native Americans.

Not much is known about this model, Gertrude Three Finger, although it's worth nothing that her traditional garment is decorated with elk teeth. Irwin worked with her multiple times. Another photo shows her and her child in a papoose a few years later and she looks as regal as ever.

This specific photo of Gertrude is a cabinet card that was made with an albumen print. It can be seen in person at the Library at the University of Oklahoma.

K'aa lani (aka Many Arrows) - Navajo warrior, 1903

By the end of the 19th century the once proud Navajo tribe had been reduced to living on reservations. Some of the men were working as "Indian Scouts" with the military, but they had to get special permission to leave their reservations.

As the second-largest federally recognized tribe in the U.S. the Navajo cover more than 27,000 square miles in the American southwest, which made it a hassle for the military to corral them even when intter-tribe communication was no easy task.

During World War 2 Navajo warriors became indispensable to the U.S. military as code talkers, soldiers who used the Navajo language to relay messages that the Japanese military couldn’t understand.

Pete Mitchell aka Dust Maker of the Ponca tribe, 1898

This photo of Pete Mitchell from the Ponca tribe was taken by Frank Rinehart, a photographer known for his work with the Native American people. His photos aren’t just pictures of people, but a look into the people who helped shape America.

Rinehart’s photos capture the personalities and dreams of his subjects, allowing the viewer to see them as more than just a different race, but as someone with interior life the same as their own.

Taken in 1898, this photo was snapped at the Omaha Indian Congress in Nebraska, the largest gathering of American Indian tribes of its kind at the time, and it hosted more than 500 members of 35 different tribes.

A Yuma man plays his flute, Arizona, 1900

The Yuma people are also known as the Quechan, and for much of their lives during the 16th, 17th, and 18th, centuries they populated Arizona and California, two parts of the United States that feel like they’d be unlivable without modern amenities, but they did it.

A warrior tribe, the Quechan people battled the Papago, Apache, and other tribes for control of the fertile flood plains of the Colorado River, the main boundary between Arizona and California.

Like any other group of people, the Quechan people also enjoyed music and art, using it to get through the hard times as well as the good.

This beautiful woman belonged to the Iroquois tribe, a group that was less defined by a bloodline and more on their shared language. Most speakers of the this language lived in the areas of Ontario and upstate New York since at least the 1500s.

Around that time the Iroquois who created an elaborate political system with a two-house legislature as well as representatives who were able to veto decisions by legislatures. The political system was essentially like that of the British Parliament and what occurs in the U.S. Congress.

In Iroquois society many of the decisions were made by women, they were believed to be the most in touch with the Earth’s power. They determined how the food would be distributed and voted on the makeup of their political system.

Chief Bone Necklace of the Lakota tribe, 1899.

The Lakota people are made up of seven tribes and the Oglala Lakota or Oglala Sioux are a small section of the group with a about 3,000 members to their part of the tribe.

A familial group of people, the Oglala Lakota exalt women above the men in their tribe. Chiefs were selected based on the mother’s clan and women decided how the food, resources, and property were to be dispersed.

After being moved several times during the 1870s the tribe settled on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, the eighth-largest Native American reservation in the United States.

Many of the earliest “Wild Westers” or “Show Indians” came from this Lakota tribe as a means for escaping the depression and impoverishment that their people faced due to be forced onto reservations.

This gorgeous couple was photographed by Alex Ross, a man with a golden eye who moved from Winnipeg to Calgary, Alberta in 1884. When he arrived he opened up a photographic studio where he took portraits of multiple First Nations people.

Ross photographed members of the Tsuu T’ina (then known as Sarcee) and the Blackfoot. The couple in this photo could have belonged to any number of tribes, with at least 48 governments in the area.

Ross’ photos provide a short, but important look into two decades of the First Nations people living in the Alberta area. His work is both gorgeous historically necessary.

This gorgeous model is none other than Goldie Jamison Conklin, a woman who grew up on the Allegany Reservation, in South Western New York before she became a model for the Cattaraugus Cutlery Company of Little Valley, New York.

Conklin was hired by the Cattaraugus Cutlery Company to help sell their line of “Indian Brand” knives and other household items through a series of postcard advertisements in which she dresses as an “Indian princess” and poses with a beaded bag that she likely made herself.

She stayed in New York, and records show that she passed away in 1974, well into her 80s.

While some Native tribes lived on small areas of land, the Blackfoot nation lived on large expanses of North America that stretched from the Saskatchewan valley in Canada to Montana.

During the 18th century the Blackfoot moved westward on foot with the use of wooden travois pulled by dogs who were transporting their effects. The tribe used horses and firearms as early as 1750 and they used them to take over and drive weaker tribes out of their way.

Before the tribe moved to reservations the Blackfoot had a massive amount of power and territory, some of which stretched to the Missouri River.

Likely one of the most well known Native Americans of the 19th century, Crazy Horse was a Lakota war leader who fought against the United States federal government in order to keep settlers away from his people’s land, but it was after a battle with another Native American that he married Black Shawl.

In 1870 Crazy Horse shacked up with Black Buffalo Woman, the wife of No Water, and after No Water tracked them down and shot Crazy horse in the upper jaw.

Black Shawl, a member of the Oglala Lakota, was sent to help Crazy Horse get back to good health. The two married in 1871 and she gave birth to Crazy Horse's only child, a daughter named They Are Afraid Of Her who passed away at a young age.

Made up of seven different groups known as the Oceti Sakowin, or the “Seven Council Fires,” these separate bands were known as the Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota depending on their dialects and these three groups were split into their own separate groups.

They began their lives in northern Mississippi before moving to South Dakota, by the late 1700s the Sioux were using horses to help expand their nation, although by the 19th century all of the space they’d taken for themselves was broken up by the U.S. government.

As the 20th century came into view the Sioux were displaced across the Dakotas, Canada, and Minnesota.

Living in the Southern Plains and Southwest United States, the Chiricahua people had a territory of 15 million acres that made up Southwestern New Mexico and Southeastern Arizona as well as land that stretched into Mexico before coming into contact with European explorers.

Many different groups are affiliated with the Chiricahua, including the Apaches, as the tribe was more concerned with keeping a loose collection of family members rather than sticking to one strident section of breeding.

This photo, taken by Frank Rinehart shows a woman named Hattie Tom adorned in some of her finest beads and looking like someone who would still be cool today.

By the end of the 19th century the Apaches were on the run from the American and Mexican militaries. The once fearsome warrior tribe was no longer the formidable group they’d once been but that didn’t stop them from fighting with every ounce of strength.

While some Apache warriors were still getting into skirmishes with two different countries, many other members of the community were simply trying to get on with their lives.

Life in the southwest meant that the Apaches who stayed in their home land had to dress to keep cool and safe under the hot sun while protecting themselves from the elements. This woman is dressed in the traditional garb of buck skin patterned with beads, inspired by their brethren in the plains.

The Great Depression hit everyone in America hard, but the Native people were among some of those who felt this generational black hole the most, although in this era the U.S. government attempted to right the wrongs of the past.

In 1934 the Indian Reorganization Act was created in order to take America’s indigenous people off of reservations and put them back on the land that they saw as home - as long as that land wasn’t privately owned.

As nice as this idea was, there was no real structure in place to stimulate the economy among Native Americans and it failed to provide a useful structure for Native politics. However, the act did help conserver communal tribal land.

As one of the largest groups of indigenous people in North America, the Cree tribe has deep roots throughout Canada and the western plains. Initially they had small tribal lands in Canada but in the 17th and 18th centuries the tribe expanded thanks to their work in the fur trade and they found themselves stretching out from east of Hudson Bay to west of Alberta.

The Cree’s numbers were depleted in the late 18th and early 19th century due to wars with the Sioux and Blackfoot followed by a smallpox epidemic that ripped through the tribe.

By the early 20th century the Cree had split into 12 different bands with their own chief, although they still worked together during times of extreme strife.

The indigenous people to Alaska are often thought of as one large group even though they’re made up of five different tribes, although they don’t use that particular word to describe themselves.

The groupings are the Aleuts, the Northern Eskimos, Southern Eskimos, Interior Indians, and Southeast Coastal Indians; the separations came from researchers who noted the cultural similarities shared by people in various regions.

In spite of their differences the groups all had to dress warmly to fight off the frigid subarctic chill and to keep their families safe. This woman’s hood may look uncovered, but it’s so warm that her baby has no problem catching some Z’s while she poses for a photo.

Not much is known about the man in this photo aside from the fact that his name is High Hawk and he’s wearing a ceremonial outfit belonging to the Brulé tribe - one of the seven bands of the Teton (Titonwan) Lakota American Indian people.

Taken by Edward S. Curtis, this photo mostly likely shows High Hawk on the plains of South Dakota, which is where the Brulé call home. Along with the Oglala Lakota this group has formed the Southern Lakota.

It’s believed that the Brulé received their name from French explorers who saw a tribe running through burning grass along the plains, thus earning them the name “Burnt” or Brulé.

The nomadic Kiowa people first coalesced into a tribe around 1650 at the northern basin of the Missouri River before migrating to the Black Hills where they lived in harmony with the Crow natives.

They moved slowly down to the Red River area of Arkansas in order to flee warring tribes who moved into their territory before making an alliance with the Comanche in 1807.

For much of their life the Kiowa roamed the plains living in the way that we tend to think Native Americans got around - they slept in teepees, ate buffalo, and gathered vegetables. In 1867 the Treaty of Medicine Lodge placed them on a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma.

An Inuit man warms up his wife’s feet in Greenland, 1890s. (photo by Robert E. Peary)

In 1891 Robert E. Peary traveled to Greenland with a party that included his wife, Josephine, and the explorer Frederick A. Cook. Peary studied the region and also made contact with the “Arctic Highlanders,” an isolated tribe who warmed up to him and even helped with further expeditions.

During his expeditions to Greenland and time with the Arctic Highlanders Peary learned a great deal about survival in a less than optimal situaton and the way that this tribe took care of one another.

After coming into contact with Peary the Highlanders became slightly more westernized and began entering into the world of business with a trading post in Uummannaq that was established in 1910.

Shaman

Shamans aren’t explicitly tied to Native Americans or indigenous American people; they’ve been a part of various cultures throughout the ages, but as the indigenous people of America have maintained a closer tie to their traditional beliefs and connection with nature as the rest of the world lost themselves in technology shamanism became an important practice as a part of their culture.

Most Americans know of “medicine men,” or traditional spiritual leaders and healers, but they’re so more than that. They promote harmony between the spiritual and natural realm while helping the people of their tribe gain a greater spiritual understanding.

Wild Horse, a wise Dakota native, 1880's

Comprised of four different bands, the Dakota people have long maintained that their tribe is all about togetherness. For generations they’ve come together as a people in order to take care of one another, to help with the crops, and keep the household lively. Yankton Dakota anthropologist Ella Deloria wrote in 1944:

The Ultimate aim of a Dakota life, stripped of accessories, was quite simple: One must obey kinship rules; one must be a good relative. No Dakota who has participated in that life will dispute that.

This kind of kinship created a community structure throughout Dakota nation that ensured no matter which village a Dakotan found themselves in they’d feel like they were home.

Whiteman Runs Him, fought in Little Big Horn, poses for a photograph in Washington, D.C. in 1910.

White Man Runs Him, a Crow scout who worked with George Custer during his 1876 fight against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne that ended up as the climactic Battle at Little Bighorn.

He volunteered to work with the U.S. Army when he was only 18-years-old and he was enlisted as a scout with a group of six Crow warriors and fellow scouts.

Following the battle, White Man Runs Him retired to a reservation in Lodge Grass, Montana, and became a minor celebrity amongst the Crow people. He passed away in 1929 in the Big Horn Valley region of Montana.

Sacagawea, a Shoshone Native American girl is best known in American history for playing a key role in Lewis and Clark's discoveries

Mostly known as the only woman on the Lewis and Clark Expedition into the American west, Sacagawea’s journey to her vaulted part of history was a long and twisted journey.

The daughter of a Shoshone chief, Sacagawea was captured by an enemy tribe as a young girl before she was married to French Canadian trapper. If that wasn’t already life changing enough she was brought into the Lewis and Clark expedition as an interpreter or their trip across the country.

In 1805 - in the middle of the expedition - she gave birth to her son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. Even though she was with child she was still one of the most integral members of the team - finding food for the group and serving as a symbol of peace.

Following the end of the expedition Sacagawea moved to South Dakota where she passed away in 1812 after giving birth to her daughter.

Native chiefs and U.S. officials bonding in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, 1891

Isn’t it fascinating that even at the end of the 19th century people were still happy to crowd around a pennant, a symbol of sports and togetherness and pose for a photo?

This meeting in South Dakota brought together multiple tribes from across the plains - the Brulé, Miniconjou, and Oglala Lakota - in an exchange of cultural information that endeared both groups of people to one another.

It’s astounding that this site, near the battleground of Wounded Knee, would end up seeing people from across the nation coming together. The area has been designated a National Historic Landmark and the site of five different reservations.

George A. Custer’s six Crow scouts pose for a photograph in 1908 standing among the tombstones on the Little Bighorn battlefield.

During the Battle of Little Bighorn General Custer employed six Crow scouts to help him defeat the Sioux, one of their major enemies along the plains. One of Custer’s scouts, Blackfoot, chief of the Mountain Crow, recalled the words of Col. John Gibbon before the battle. Blackfoot explained that Gibbon said through an interpreter:

If the Crows want to make war upon the Sioux, now is their time. If they want to drive them from this country and prevent them from sending war parties into their (Crow) country to murder their men, now is the time.

Prior to this battle the Crow were under near constant barrage from the Sioux and Cheyenne - tribes that deeply outnumbered them. The Crow wanted to grow their tribe and expand their reservation. Before the battle Blackfoot said that joining with the U.S. military was the only way to get what they wanted.

Colorized photo of Chief Little Wound of the Oglala Lakota and his family, 1899

During the late 1800s Little Wound served as the chief of the Eastern Oglala, a tribe that he lead into battle of Massacre Canyon on August 5, 1873. This was one of the final battles between the Pawnee and the Sioux and the final large scale skirmish between Native tribes in the states.

Later in life Little Wound became an advocate for the Ghost dance movement within the Lakota while thumping for peace with the European Americans who made their way across the plains.

Much of his final years was taken up by attempting to speak for peace, something that likely appealed to him after overseeing so many battles throughout his youth.

Chief Red Bird of the Cheyenne, 1927

Growing up on the plains, Red Bird was a part of a strong tradition of an indigenous nation who came about speaking the Algonquian language. The Cheyenne tribe was made up of two different groups - the So’taeo’o and the Tsitsistas.

Even though they were a heterogeneous mix of tribes at their formation, by the 19th century the Cheyenne were a unified tribe, with a well built structure based on their ritualistic ceremonies... they were unbreakable.

By this time the Cheyenne had changed from their sedentary ways to a nomadic lifestyle that took them across Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, and South Dakota.

Chief Clinton Rickard. May 19 1882 -June 14 1971 - Tuscarora nation

Born on the Tuscarora Reservation in New York in 1882, Clinton Rickard grew up to be a farmer after fighting with the U.S. Calvary during the Philippine insurrection following the Spanish–American War.

By 1926 Rickards founded the Indian Defense League with Chief David Hill, Jr. and Sophie Martin in order to allow Native Americans from Canada and North America to travel unencumbered between the two countries.

Rickard continued to fight for Native rights until his death in 1971. He went so far as to insist that Native Americans volunteering to join the Armed Forces during World War 2 do so as Natives and not U.S. citizens.

As a chief of the Blackfoot Nation, Chief Duck oversaw four smaller groups across the plains - three in Canada and one in Montana. Obviously he had help, Duck wasn’t the only chief at the time, that would have been disaster for this group of powerful plains Natives.

By the early 20th century the Blackfoot had sold much of their land to U.S. officials who turned their space into Glacier National Park. The property lines laid out at the time are essentially the same now as they were then.

This era saw the Blackfoot culture change as they moved towards a more sedentary lifestyle instead of the nomadic ways that they practiced for generations.

Black Eagle Ogalala Lakota medicine man, 1932

One of the most fascinating things about the Lakota medicine men is that they weren’t simply shamans and caretakers of their village, but they also acted as court jesters and satirists, mocking much of the culture around them.

These men were known as the Heyókȟa. They did everything backwards, upside down and contrarian to popular thought whether it meant riding their horse backwards or wearing their clothing inside out.

The existence of the Heyókȟa was meant to make people ask questions about themselves and examine their doubts, fears, hatreds, and weaknesses. These shamanistic men played an important role is helping their people heal emotional pain.

An Arapaho family poses outdoors near a teepee.

Living across the plains of Colorado and Wyoming the Arapaho people have a strong oral storytelling tradition that’s only rivaled by their love of agriculture.

In the 1830s the group became nomadic, living in teepees and traveling by horseback while growing vegetables like corn, beans, and squash while trading with the Mandan and Arikara tribes.

There was much ceremony around the lives of the Arapaho, everything had a special meaning to the people, whether it be a bead or a feather. They danced for the sun as a prayer for healing, both physically and emotionally. Today they reside in Oklahoma and Wyoming.