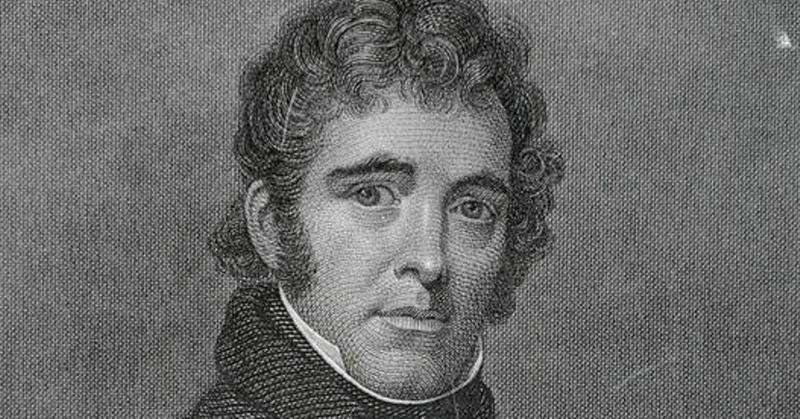

Richard M. Johnson, The Most Colorful Vice President Of The 1800s

By | June 26, 2022

The United States has had its share of characters serving as vice president, but let's face it, if we go back just a few elections, we tend to forget who the vice president was. One of the most surprisingly forgotten is Richard M. Johnson, who served under President Martin Van Buren from 1837 to 1841. Before you ask, yes, there was definitely a reason he only stuck around one term.

Richard M. Johnson

Richard Mentor Johnson first dipped his toe into politics in 1804, when the 22-year-old was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives. The state constitution prohibited members under the age of 25, but Johnson was so popular that everyone simply chose to forget that little rule. When he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives two years later, he just barely squeaked by, turning 25 just time for the congressional session to begin.

In 1813, during the increasingly inaccurately named War of 1812, Johnson gained national fame for killing the Native American war hero Tecumseh, so when he campaigned for the vice presidency in 1836, he used the campaign slogan, "Rumpsey Dumpsey, Colonel Johnson Killed Tecumseh." After he fell short by a single electoral vote (vice presidents were elected separately from the president back then), the Senate invoked the 12th Amendment to elect him, marking the only time a vice president was voted in by the Senate.

Johnson's Personal Life

Johnson was engaged to be married when he was just 16 years old, but his mother forced him to end the relationship even though his ex-fiancée soon gave birth to his child, a daughter named Celia who was raised by the Johnsons. After his father died in 1815, he began a relationship with one of his inherited slaves, a woman named Julia Chinn. Johnson couldn't legally marry her, but he referred to her as his wife and they lived as a married couple, which scandalized the pre–Civil War South.

Johnson was similarly open-minded about his choice of friends, including fellow Kentuckian John Cleves Symmes, Jr., who loudly believed the Earth was hollow and the center of the planet was inhabited by highly advanced mole people. After he was elected vice president, Johnson even asked the Senate on behalf of his friend to seek congressional funding for an expedition to the North Pole to find the secret entrance to Middle Earth and meet the mole people, but surprisingly, he was shot down.

Life After The Vice Presidency

Johnson quickly found life as America's vice president rather boring, so in 1837, he took a nine-month leave of absence from his duties, returned to his hometown, and opened a tavern on his farm. This, plus the generally perfunctory approach he took toward his duties, led Van Buren to politely inform Johnson that his services were no longer needed at reelection time, so he returned to Kentucky to run his tavern and launched a series of failed attempts to regain political office. In 1850, he was finally elected once more to the Kentucky House of Representatives, but just two weeks into his term, he died of a stroke.