Smallpox: The First Bioweapon

By | June 23, 2021

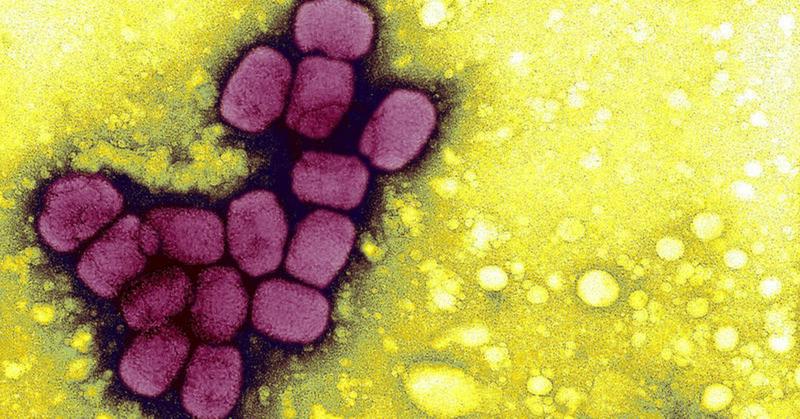

Smallpox is an extremely infectious and deadly disease, wiping out up to 30% of those unlucky enough to catch the virus. By the 1700s, people began figuring out how the disease spread and how to prevent it through inoculation (thanks in large part to an enslaved man named Onesimus), but this opened the door for less scrupulous people to weaponize the virus in times of conflict.

During the Revolutionary War, the British used the knowledge of contagion and inoculation to weaponize smallpox numerous times, especially against people of color. On June 15, 1776, The Virginia Gazette told of such a scheme:

We learn from Gloucester that Lord Dunmore has erected hospitals upon Gwyn's island [sic] and that they are inoculating [black residents] for the smallpox. His lordship, before the departure of the fleet from Norfolk harbour, had two of those wretches inoculated and sent ashore, in order to spread the infection, but was happily prevented.

Likewise, famed British General Charles Cornwallis, in his desperate efforts to cling onto those last strands of British control over the colonies, also used black soldiers who had joined the British side with hope of obtaining freedom as bioweapons. During the Battle of Yorktown, Cornwallis sent ailing black soldiers out "in the most deplorable condition, perishing with famine and disease" toward enemy lines to spread the infection to the American army, leaving the Americans the choice to either receive them and be infected or likewise cast them away to die in the field alone.

Of course, the most famous case of intentionally spreading smallpox during wartime is the 1763 incident at Fort Pitt in the heavily contested Ohio country (present-day Pennsylvania), where the British supposedly gave out blankets contaminated with the virus to the Native Americans. Many historians still mark this as the first credible case of biological warfare in world history, although there were rumors of earlier events. In 1757, the Potawatomi suspected the British were willfully at fault for an outbreak that occurred just after the Battle of Lake George. Likewise, in 1770, the Ojibwas accused European fur traders of purposefully infecting them by means of a contaminated flag.

However, Fort Pitt stands out due to the availability of primary documentation and the blatancy of their stated intentions. Like, they did not try to hide it at all. In an offshoot of Pontiac's War in which Native tribes hoped to contain and push back British incursion into their lands, the Shawnee attacked Fort Pitt and surrounding villages in summer 1763. With villagers and military alike in such close quarters inside the fort, a gruesome outbreak of smallpox occurred. On July 13, British Colonel Henry Bouquet sent a letter to his general, Jeffrey Amherst, about the ongoing difficulties with the Natives, with the postscript cementing their place in the history books forever:

P.S. I will try to inoculate the Indians by means of Blankets, that they may fall into their Hands, taking Care not to get the disease myself.

Amherst replied three days later:

You will Do well to try to Inoculate the Indians by means of Blanketts [sic], as well as try every other method to Extirpate [sic] the Exacerable Race.

Even more disturbing, when Delaware warrior Turtle Heart came to Fort Pitt on diplomatic business, the British commanding officer told him to "take care of their women and children" just before giving them "two blankets and a handkerchief out of the smallpox hospital." Clearly, they knew the dignitaries were in contact with civilians, putting not only them but the greater Native community in mortal danger. It is also noteworthy that this effort was put forth on June 24 and carried out by Captain Ecuyer with such little secrecy that the trader's Captain Trent wrote it down in his diary along with the commentary, "I hope it will have the desired effect." The diary is further backed up by a Fort Pitt invoice sent that month, which includes:

To Sundries got to Replace in kind those which were taken from people in the Hospital to Convey the Smallpox to the Indians Viz':

2 Blankets @ 20/ £2" 0" 0

1 Silk Handkerchef.. . . . 10/

& l Iinnen do: . . . . . . . . . 3/6 0" 13" 6"

This means that Fort Pitt had already infected the Natives weeks before Bouquet replied to General Amherst about the scheme. The lack of secrecy and disregard for permission again calls into question the supposition that this episode was in fact the origin of biological warfare. Was this the first time they did it or just the first time they got caught?

We may never know to what extent smallpox was used as a bioweapon in the past, but we can all rest easy knowing the virus was declared eradicated by the World Health Assembly in 1980, thanks to the success of vaccinations.