Spanish Flu: The Pre-Coronavirus Pandemic That Killed Millions In 1918

By | February 29, 2020

Long before the coronavirus, the Spanish flu was one of the first recorded pandemics, infecting at least 27% of the Earth's population at the time and killing 3–5% of them. Reaching as far as the Arctic, this pandemic heralded the beginning of a more connected, albeit frightening, world whose complications we're still dealing with today.

Spanish Flu Killed More Adults Than Any Other Flu

Deaths from the flu tend to be limited to those who already have an immature or weakened immune system—basically, the very young or the very old. The Spanish flu, like today's coronavirus, was different. It wiped out just as many (if not more) young adults as infants and seniors, resulting in a higher mortality rate than had been seen in previous influenza outbreaks.

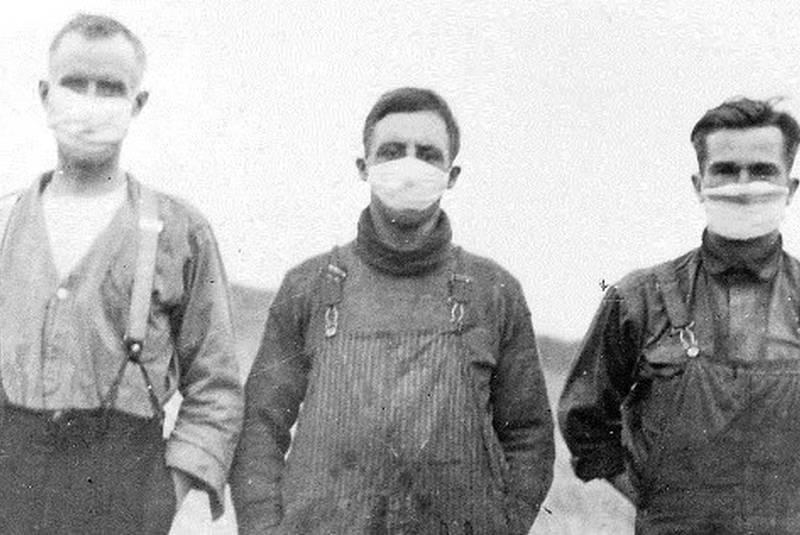

It wasn't just that the flu was super intense, although it definitely was. What really pushed this outbreak into pandemic territory was its ease of transmission and the poor hygiene and overcrowding of the medical camps ironically set up to treat it. Much like the coronavirus, the growing convenience of international travel helped it spread far beyond the distance that it normally would.

Why Was It Called The Spanish Flu?

Although the H1N1 virus (which you might recognize by its rebranding as the "swine flu" in 2009) became known as the Spanish flu, its only relationship to Spain was political. In reality, "patient zero" is now known to be a Kansas Army cook named Albert Gitchell, who was diagnosed on March 4, 1918. From there, it spread throughout the world thanks to movements of soldiers fighting in World War I. However, wartime censors quelled reports of the flu in Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and the United States, encouraging the media to blame the illness on Spain in retribution for the country's neutrality regarding the war. In his book on the pandemic, Albert Marrin explains the media blackout of the era and its relation to the war as an attempt to maintain morale in Allied countries:

For propagandists, whatever promoted the Allied cause was true, whether factual or not. What counted was the noble end—victory—not the sordid means of achieving it. 'Truth and falsehood are arbitrary terms,' declared a CPI official. 'There is nothing in experience to tell us that one is always preferable to the other ... There are lifeless truths and vital lies ... The force of an idea lies in its inspirational value. It matters very little if it is true or false.

China Was Less Affected By The Flu Of 1918

You'd think that with such a dense population, a country like China would be especially susceptible to a global pandemic, but it's one of the regions that was the least affected by the Spanish flu. China was definitely hit by the pandemic, but the percentage of deaths was much lower than in other countries. Some flu-truthers believe that this means the pandemic originated in China, but like most truthers, they have no evidence to back up that assertion. It's most likely that the Chinese people were resistant to the virus thanks to a flu outbreak that occurred earlier in the decade. This was, unfortunately, not the case for the coronavirus pandemic, which hit China harder than anywhere else.

World War I Hastened The Spread Of The Illness

While the Chinese and Spanish were blamed for the spread of this deadly flu, the real culprit was that intangible baddie that we call war. Once World War I was underway, troops from all over the world intermingled in trenches and camps, which not only increased transmission of the illness but enabled it to mutate into new and more dangerous varieties. While the world was fighting no war in 2020, modern transportation allowed the public to flit from country to country for fun, not battle, resulting in similar transmission patterns for the coronavirus.

At the time, many soldiers were suffering from malnutrition and the stress of war, which only helped the virus wipe them out. Those who survived the initial wave of the illness spread it around to other troops, friends, and even family if they were lucky enough to return home. The 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic: The History and Legacy of the World’s Deadliest Influenza Outbreak explains:

As the early outbreak at Fort Riley suggested, the primary breeding ground for the influenza consisted of army camps that were springing up all over America in the early days of 1918. America had entered World War I the previous October, and many young men were anxious to do their part and join the fight. As a result, the camps soon became overcrowded with recruits and service veterans brought in from all over the country to train them.

The Mortality Rate Was Stunning

In the United States alone, nearly 20% of the population of 105 million became infected, with nearly half a million deaths. According to the World Health Organization, around 3% of people who contracted the flu died. That might not sound like a lot, but it's close to 30 million people worldwide. Other estimates place the death toll closer to 50 or even 100 million. The coronavirus has a similar death rate, it just hasn't infected as many people—yet.

One of the reasons the Spanish flu was so deadly was the tricky way that it presented in patients. Rather than first showing flu-like symptoms, as with the coronavirus, people bled from their ears or noticed small red dots suddenly crop up on their skin. Patients were misdiagnosed with everything from cholera to typhoid to a hemorrhage of the mucus membranes.

After Two Massive Spikes, The Spanish Flu Disappeared

From 1918–1919, the pandemic mostly killed relatively young adults. No one knows why the illness spared the young and the old, but for whatever reason, 99% of deaths in the United States were people under the age of 65. Following the peak of the pandemic in late 1918, however, the number of people suffering from the illness nosedived. It disappeared as suddenly as it arrived. John M. Berry writes that in the week ending on October 16, 4,597 people died of the flu in Philadelphia, but by November 11, there were almost no deaths in the city. It's believed that the flu simply tore through its victims and that was that. Let's hope the same happens to the coronavirus before it kills millions.