Thomas Nast: Father of The American Political Cartoon

By | September 23, 2020

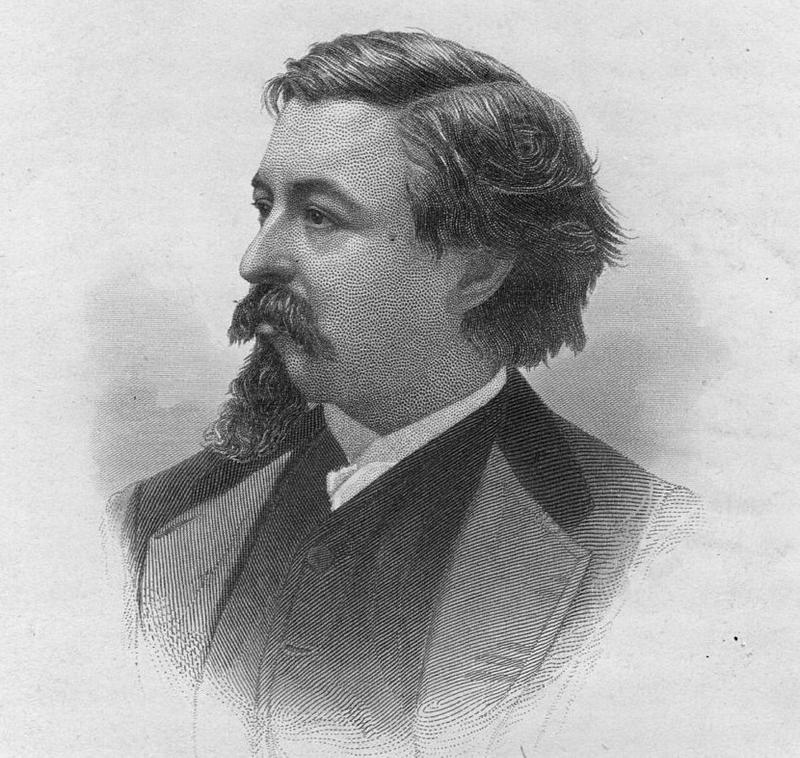

It is true that oftentimes, a picture is worth 1,000 words. It is also true that sometimes, the antics of our elected officials are so ridiculous that they are almost laughable. With both of these thoughts in mind, a German-born artist made a major impact on the political scene of New York City and the entire United States in the last half of the 19th century. Thomas Nast can rightfully be called the father of the American political cartoon as well as the symbols that define politics to this day.

Who Was Thomas Nast?

Thomas Nast was born on September 27, 1840 in the German town of Landau, but he didn't stay in Germany long. When he was six years old, he and his family immigrated to the United States, settling in New York. From a young age, Nast showed his talent as an artist, taking art classes at the National Academy of Design in New York City. When he was only 15, he took a job as a draftsman for a publication called Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, and a few years later, he landed at Harper's Weekly.

Thomas Nast's Political Cartoons

When the American Civil War broke out, Nast used his artistic ability to voice his support for the Union cause. He was so good at depicting the complexity of emotions in one simple drawing that President Abraham Lincoln called him "our best recruitment sergeant." Nast wasn't quite as friendly with Lincoln's successor, however, depicting Andrew Johnson as a power-hungry autocrat who was determined to take away the rights of citizens.

Nast went on to shine a light on the corrupt and illegal dealings of New York City Democratic Party leader William Marcy Tweed, also known as "Boss Tweed," and his Tammany Hall political machine with powerful cartoons like "The Tammany Tiger Loose" and "Group of Vultures Waiting for the Storm to Blow Over," both released in 1871. One cartoon, depicting Tweed fleeing the country ahead of corruption charges, was even used to identify Tweed in his hideout in Spain, where—yes—he had fled the country.

Thomas Nast, The Symbol Maker

In his popular political cartoons, Thomas Nast used a lot of symbolism to get his message across. For Tammany Hall, he often used a tiger. For the nation's two largest political parties, the Republicans and the Democrats, Nast created symbols that are still in use today. Andrew Jackson, the first Democratic president, was often called a jackass by his opponents, so Nast transformed the jackass into a donkey to symbolize the Democrats. He chose the elephant to represent the Republican Party because of the Civil War expression "seeing the elephant," which originally meant seeing combat but eventually came to mean that a person had hands-on experience with something. It's pretty clear which one he preferred.

Nast's contributed to American culture weren't limited to politics, however. Nast first gave a face to the fictional and ambiguous Uncle Sam character in the late 1860s. He continued to hone the image for several years, and the end result was the tall, lanky figure with a long white beard, top hat, and stars and stripes that persists to this day. Nast even invented Santa Claus—well, the modern image of him, anyway. For his cartoon about Santa that appeared in the January 3, 1863 issue of Harper's Weekly, marking the first appearance of the jolly old elf that we know today, Nast referred to Clement Clarke Moore's 1823 poem, "A Visit from St. Nicholas." Popularly known as "'Twas The Night Before Christmas," Moore describes Santa as having a full white beard, a red suit, twinkling eyes, and a belly that shook like a bowl full of jelly.

The Fall Of Nast

For a while, it seemed no figure in politics was more influential than Thomas Nast. Political historians have even identified his cartoons as one of the key deciding factors in six presidential elections held between 1864 and 1884. Shortly thereafter, however, Nast's popularity began to wane, and he left his job at Harper's Weekly. He made a few bad investment decisions that left him deep in debt, and by 1902, he was nearly destitute. He applied for a job with the State Department, and luckily, President Theodore Roosevelt was a huge fan of his work—at least, it seemed lucky at the time. Roosevelt offered Nast the position of consul general in Ecuador, but in Central America, Nast contracted yellow fever and died. His body was returned to the United States and laid to rest in New York City's Woodlawn Cemetery.