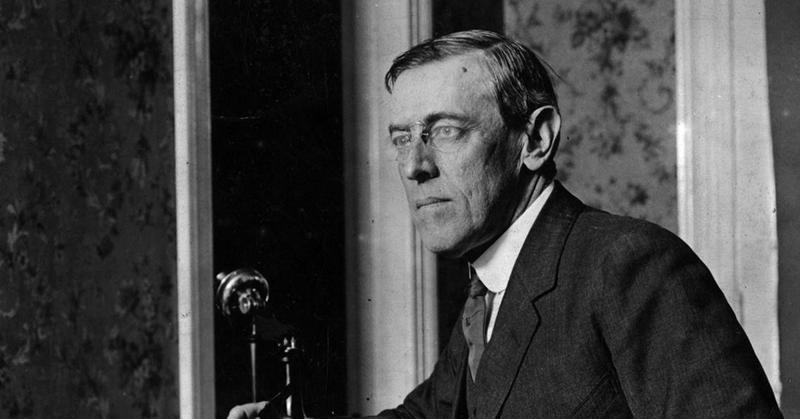

How Woodrow Wilson Planned To Hack His Own Election For The Good Of The American People

By | July 31, 2020

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson was pretty sure that he was on his way out of the White House, and although he ran for reelection, he apparently wanted to get out of there as fast as possible. It's not that he was a sore loser or couldn't stand the sight of those carpets any longer—he felt the inauguration process was objectively too long, so he came up with a scheme that he hoped would help the country even if he wasn't the Commander-in-Chief. Basically, Wilson tried to hack the election to make sure his opponent could get to work as soon as possible.

The Inauguration Period

Today, a newly elected U.S. president has to wait about two months until they can bust down that White House door and start shaking things up. It provides time for them to put the gears of their political strategy in motion and their predecessor to empty the White House of their presence. Before 1916, however, that transition took four months, which is a lifetime in politics. Instead of strategizing and getting to know the lay of the land, the new Commander-in-Chief, plus their staff and family, had to spend that time traveling to Washington, D.C., often by horse or wagon. With the advent of modern transportation and America becoming a greater foreign power in the early 20th century, however, Wilson realized that a four-month transition was too long.

Charles Hughes's Vicious Campaign

During his first term, Wilson shepherded a series of popular, progressive laws that put him in a prime position to dominate the next election. Still, he believed that the only reason he won the 1912 election was because Theodore Roosevelt ran as the candidate for the Bull Moose Party, thus splitting the Republican vote. Without the split, he was certain that he was going home—and not without reason.

The rift in the Republican Party wasn't completely repaired by the 1916 election, but they put aside their differences for the time being, determined to win the White House. Even Roosevelt came crawling back, but he was rejected as a candidate in favor of Charles Evans Hughes, an associate Supreme Court justice and former governor of New York. Rather than split the vote again, Roosevelt opted to just sit this one out.

The Hughes campaign came out guns blazing against Wilson, attacking his decision to stay out of the conflict in Europe that was quickly brewing into World War I and remarrying so quickly after his wife passed away in 1914. Even though Hughes was seen as a kind of political mannequin with no personality to speak of, Wilson knew that the reenergized Republican Party had his number.

Hacking The Election

Although Wilson and Hughes were at odds both politically and personally, the race was extremely close, and the President felt that the best thing for the American people would be to get out of the way and make sure that Hughes could start enacting policy as quickly as possible. On November 5, two days before the election, Wilson wrote a letter to the secretary of state, Robert Lansing, to explain his plan—basically, installing Hughes in Lansing's position and then resigning en masse so the presidency would automatically fall to Hughes, in accordance with the the Presidential Succession Act of 1886. He wrote:

Throughout the campaign I have thought again and again what my duty would be should Mr. Hughes be elected. Four months would elapse before Mr. Hughes could take charge of the affairs of the Government, and during those four months I would be without such moral backing from the nation as would be necessary to steady and control our relations with other governments. I would be known to be the rejected, not the accredited spokesman of the country; and yet the accredited spokesman would be without legal authority to speak for the nation ... [What] I have in mind is dependent upon the consent and cooperation of the Vice President; but if I could gain his consent to the plan I would invite Mr. Hughes to become Secretary of State and would then join the Vice President in resigning, and thus open to Mr. Hughes the immediate succession to the Presidency.

Foiled By Success

Aside from Wilson, his wife, and Lansing, no one knew about the President's scheme, and they wouldn't until Lansing's biography was released nearly two decades later. The race was tight one, but Wilson took the electoral college by only 23 votes and went on to lead the U.S. through World World I and into Prohibition. His inauguration hack never came to fruition, but at least he tried.