Battle Of Antietam: The Second Deadliest Day In American History

By | December 13, 2020

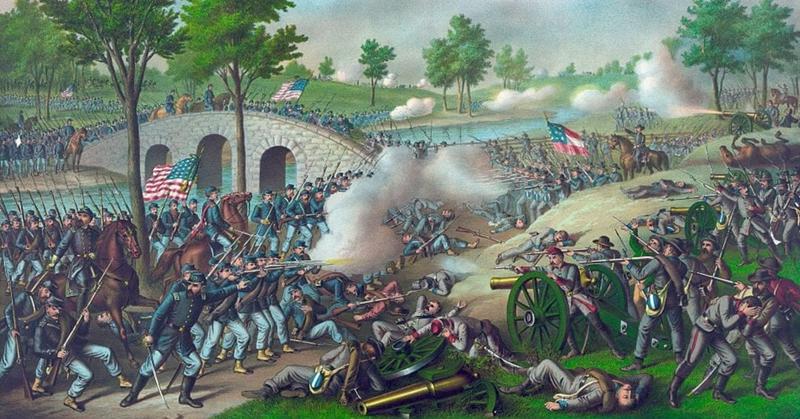

When 3,650 people died on September 17, 1862, it became the single deadliest day in American military history and the second deadliest day the country has ever seen at all, just behind the Galveston hurricane of 1900. The Battle of Antietam, also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, turned the tide of the American Civil War, in part due to the staggering number of casualties and in part thanks to the new technology of photography that brought the horrors of the battlefield to newspapers across the country. While the Battle of Antietam was a key moment in the Civil War, it was also an event filled with missed opportunities.

Both Sides Needed The Win

The Union Army assumed that victory over the Confederacy would be swift and easy, but as summer 1862 wore on, it became clear that the Southern states were a formidable foe. The Confederacy hammered this home with their defeat of Major General John Pope and the Union troops at the Second Battle of Bull Run. President Abraham Lincoln had his Emancipation Proclamation ready to announce, but he knew it would carry much more weight if it came on the heels of a decisive Union victory.

To make matters worse, Lincoln was facing a mid-term election that threatened to flip control of Congress from Lincoln's Republicans to the anti-war Democrats. Confederate General Robert E. Lee was well aware of this, of course, and hoped a few more Union defeats might swing the mid-term election to the Democrats, thus yanking Lincoln's congressional support.

General George B. McClellan, a Questionable Leader

The Battle of Antietam was all important for Union General George B. McClellan, who had planned to attack the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia the previous summer only to be derailed by a counterattack from Lee. Sensing an opportunity to kick the Union army while they were down, Lee moved his troops north into Maryland and took over the town of Frederick, where he laid out his plans to push his forces into Northern territory and split his army in two to take Hagerstown, Maryland and Martinsburg, West Virginia. He called his plan Special Order 191.

As Lee's men marched out of their camp in Frederick, however, someone made a critical mistake. General McClellan's army happened upon the abandoned Confederate camp, and Sergeant John M. Bloss and Private Barton W. Mitchell discovered three cigars loosely wrapped in a sheet of paper lying on the ground. Likely hoping for nothing more than a good smoke, they soon realized the paper contained Special Order 191. An ecstatic McClellan immediately began strategizing to thwart Lee's battle plans, but at the same time, Lee discovered his plans were missing and hurried to reunite his forces.

Prelude To Battle

On September 14, Confederate Generals D.H. Hill and James Longstreet and their units engaged Union troops near South Mountain outside Sharpsburg and sustained heavy casualties, much to their surprise. When Lee heard of this, he initially ordered a retreat back into Virginia but changed his mind when he found out that Confederate General Stonewall Jackson had seized Harper's Ferry. Armed with this information, Lee ordered his army to regroup in Sharpsburg at a small river known as Antietam Creek.

As the Sun rose over the farmlands on either side of Antietam Creek on the morning of September 17, Generals Hill and Longstreet lined up their men on the west side of the creek while the rest of the Confederate troops set up a left flank and watched as General McClellan's much larger forces assembled along the east bank. The Union troops fired the first shots that triggered the bloodbath to come, and the 30-acre cornfield belonging to farmer David Miller was turned into a puddle of carnage.

The Bloody Lane

With his force of about 2,600 men, General Hill dug into one of the embankments of a small farm lane known as the Sunken Road and prepared to fight the more than 5,500 men of a Union unit under the command of Major General William H. French. After three hours of fierce, close-range fighting, the Sunken Road ran red with the blood of the fallen. Nearly 5,000 men were either killed or injured along this small road that was henceforth called the "Bloody Lane."

At another site nearby, a small unit of 500 Confederate soldiers held off wave after wave of assaults from the Ninth Corps under the command of Union General Ambrose Burnside. After three hours of fighting, Burnside and his men finally took the bridge, only to be beaten back by Confederate reinforcements that arrived in the nick of time.

After 12 hours of intense fighting, night fell over the bloody farm fields of Antietam, and commanders on both sides retired to remove the staggering 23,000 wounded to makeshift battlefield hospitals and regroup their remaining men.

The Aftermath Of The Battle Of Antietam

The day after the Battle of Antietam, General Lee mobilized his men to retreat back to Virginia, and General McClellan chose not to attack the battered and limping Southerners, even though it might have put an end to the Confederate Army once and for all. He later defended this action (or inaction), insisting that he had accomplished his mission of booting the Confederates out of Maryland and preventing them from claiming a victory on Union soil, but President Lincoln was furious that McClellan wasted the ideal opportunity to finish them off. On November 5, 1862, Lincoln officially relieved McClellan from his command.

From a historical perspective, the Battle of Antietam was a draw with no clear winner, but Lincoln used the battle as a rallying point, claiming the Union soldiers kept the Confederates from advancing into the North. Supposed victory in hand, he released his Emancipation Proclamation five days later, and the Republicans retained control of Congress after the mid-term election.

Two days after the battle, photographer Alexander Gardner took a series of 70 photographs of the dead soldiers at Antietam that still hadn't been buried. Photography was still a relatively new technology in 1862, and his photos marked the first time an American battlefield had been photographed in such detail. The black-and-white images shocked the public with their graphic depiction of the horrors of war and tragic losses at the Battle of Antietam.