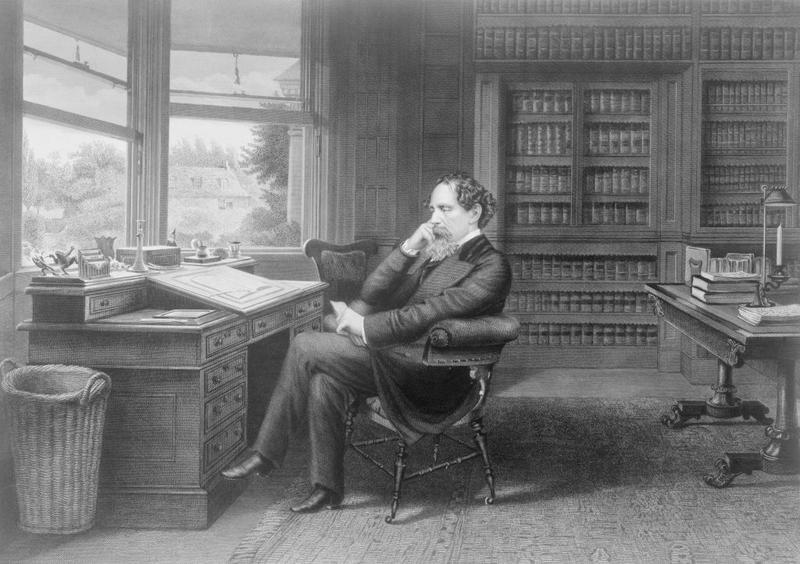

Charles Dickens: Stories, Biography, & Things You Didn't Know About The Literary Titan

By | February 5, 2021

Today, Charles Dickens is most remembered for his holiday classics and orphan rhapsodies, but there was more to the master of Victorian fiction than literature. He rescued passengers from a train wreck, busted ghosts, aided the search for a lost Arctic explorer, and rivaled the great William Shakespeare in coining new words.

Dickens's Early Years

Dickens was born in southern England on February 7, 1812 as the second of eight children. He later recalled an idyllic childhood of roaming the English countryside and exploring abandoned castles with his siblings, but the family was often financially unstable. In 1822, they moved to one of London's poorest neighborhoods, and two years later, Mr. Dickens went to debtor's prison, forcing the 12-year-old Charles to drop out of school and take a factory job to keep the family afloat. The experience at the dilapidated, rat-infested factory was eye-opening for the young Dickens, but fortunately, his father received an inheritance that paid off his debts and Charles was allowed to return to school.

Dickens always had a knack for storytelling, but his father hoped he would become a lawyer, so he spent a year as a junior clerk in a London law office as a teenager but mostly used his time there to learn shorthand. Once he mastered it, he left the law office and began reporting on the happenings in Parliament for the Morning Chronicle while publishing his first short stories on the side under the pseudonym "Boz," a character in the 1766 novel The Vicar Of Wakefield. (Dickens must have really admired this Oliver Goldsmith novel, because he mentioned it in A Tale of Two Cities, too). Readers enjoyed Boz's stories so much that in 1839, Dickens published a collection of his writings in a book called Sketches By Boz.

A Bit Of An Odd Bird

In his day, Charles Dickens was politely considered "eccentric," but today, he would probably be diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder. He had a habit of always touching objects three times, believing it was unlucky to touch an object only twice, and reportedly combed his hair at least 100 times per day. He also always slept with his head pointed north and vigilantly avoided bats, believing they were bad omens.

It was far from his only superstition. As you might have guessed from one of his most popular novels, Dickens was keenly interested in ghosts. In addition to attending seances and visiting with mediums, he joined the exclusive, invitation-only Ghost Club, whose members included William Butler Yeats and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. They tooled around together, investigating hauntings that they usually dismissed as hoaxes, which actually marked them as unusually skeptical among their peers. Unlike Dickens's other quirks, his spectral activities weren't considered weird during the spiritualism craze of Victorian England.

For all his fuss over bad luck, however, there was one such symbol he was perhaps a little too into: ravens. Specifically, his pet raven, Grip, who he found so amusing that he wrote him into his 1841 novel Barnaby Rudge. It's believed that Edgar Allan Poe based the eponymous character of his poem "The Raven" on Dickens's description of the bird in the novel. Sadly, shortly before the publication of Barnaby Rudge, Grip died after eating some lead paint chips (no word on how many times he touched them). Dickens was inconsolable, stuffing and mounting the bird and replacing him with a succession of ravens, all named Grip. Dickens had a pretty general obsession with his pets: He was also quite fond of his cat, Bob, to the point that when the cat died in 1862, Dickens had one of Bob's paws removed and fashioned into the handle of a letter opener, which is still on display at the New York Public Library.

A Taste For Danger

Wherever danger was, Dickens seemed to be around, and he had ample opportunity in the time before seat belts and G.P.S. In 1845, English explorer Sir John Franklin and his crew of more than 100 men disappeared while searching for the fabled Northwest Passage through the Arctic, and while the whole country prayed, Dickens made it his mission to help, writing articles on the expedition and lecturing to raise money for the rescue effort. It wasn't quite as heroic as it sounds: During his talks, Dickens often used racist stereotypes to blame the Inuit people for the disappearance of Sir Franklin's ships.

Twenty years later, Dickens was on a train home from France when it derailed on a bridge, injuring him and forcing him to gingerly exit his rail car as it dangled from the tracks. Not content to escape with his life, he found the conductor and asked him for the keys to seven passenger cars that had fallen into the river below. Once everyone was out, Dickens climbed back into his rail car—which was still dangling from the bridge—to retrieve his manuscript for Our Mutual Friend.

Dickens's Legacy

Charles Dickens was one of the first novelists of Victorian England to use his craft as a vehicle for social change. His fables of class disparity and abuses of social power indirectly but unquestionably contributed to the passage of social reforms in England, and he even joined forces with a millionaire heiress named Angela Coutts to open a home for "fallen women," including unwed mothers, homeless women, former sex workers, and women recently released from prison. Dickens took a hands-on role in the facility, dealing with building maintenance, record keeping, hiring staff, and even screening women before they were admitted into the home, after which they were often sent to British colonies in Canada, Australia, or South Africa to turn their lives around.

If you've ever cursed your favorite TV show for ending a season on a maddening cliffhanger, you can thank Dickens. Since most of his stories were written as serials, he had to give the reader a reason to buy the next issue, so he perfected the art of the cliffhanger. When you read Oliver Twist or David Copperfield, for example, you will notice that many chapters or sections end on such unresolved calamities. Dickens was so adept at using cliffhangers that in 1841, American fans crowded the docks of New York harbor, asking passengers arriving from England to tell them the ending of The Old Curiosity Shop, which hadn't yet been released in the U.S.

Dickens is also responsible for hundreds of words that we still use today. Over the course of his literary career, he coined a whopping 247 words, including "fluffiness," "dustbin," "manslaughter," "butterfingers," and "the creeps."

Dickens's Personal Life

Modern-day medical doctors believe Dickens suffered from epilepsy. Interestingly, several of his characters also suffered from neurological conditions, including Monks in Oliver Twist, Bradley Headstone in Our Mutual Friend, and Guster in Bleak House. Dickens's own experience with epilepsy may have informed his creation of these characters.

Dickens married Catherine Thomson Hogarth on April 3, 1836, but she couldn't be said to be the love of his life. That honor went to her younger sister, Mary, who moved in with the couple when she was 17 soon after they were married, along with Dickens's younger brother, Frederick. If the plan was for Frederick and Mary to fall in love, it failed. Instead, Dickens fell for his young sister-in-law, who soon fell tragically ill and died in his arms in 1837. It's unclear if Mary reciprocated his feelings, but Dickens was so distraught by her death that he stopped writing for a time, missed key deadlines, and moved his family out of the house where she died.

Twenty years later, the 45-year-old Dickens hired an 18-year-old actress named Ellen Ternan for a play he was co-writing and soon fell in love with the beautiful teen. He declared that his wife had become "fat and boring" after 10 children, but divorce was too scandalous to consider, so Catherine took one of her children and simply left. Dickens was left with the remaining nine kids, but Catherine's other sister, Georgina, moved in to care for them.

Although Dickens and Ternan couldn't marry, they remained together until his death, but even that was not enough to make Dickens forget about his beloved Mary. Prior to his death on June 9, 1870, he declared his intention to be buried next to his long-dead sister-in-law, but for whatever reason, his wishes weren't honored. Instead, he was buried in Poet's Corner at Westminster Abbey.