History Of Tear Gas: When The U.S. Gassed Their Own Citizens

By | June 1, 2020

Tear gas, mace, pepper spray—we see them being used pretty much every day on the news without knowing exactly what they are. Essentially, tear gas is a chemical weapon that causes skin and eye irritation, respiratory problems, and blindness. It's not good. The effects of tear gas can be so harsh that its use has been banned in warfare, but it's still used by police in countries like the United States and Australia for crowd control. This nasty chemical has a violent history dating back to the 19th century, but it only recently (historically speaking) started infiltrating our streets.

Tear Gas Isn't A Gas

Despite its straightforward name, tear gas isn't a gas. It's more of a powder or an aerosolized solid that attacks mucus membranes and makes it hard to breathe or see within a minute of exposure. When the powder hits the air, it gloms onto any bit of moisture it can find, whether that's your tears, sweat, saliva, mucus, or even the products you use in your hair. Your chest tightens, you can't see, and as your body attempts to flush your orifices to get you back to normal, the symptoms get worse.

Gassed In The U.S.A.

Tear gas wasn't designed to be deadly; it was just supposed to incapacitate people long enough to kill them with other weapons. After the Hague Convention in 1899 banned projectiles whose sole purpose was "the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases," French scientists concocted a less deadly version of the outlawed poison gas. Apparently, if it didn't kill or at least intend to kill, it was okay by the Hague. This rule was ratified by all of the major world powers except for the United States.

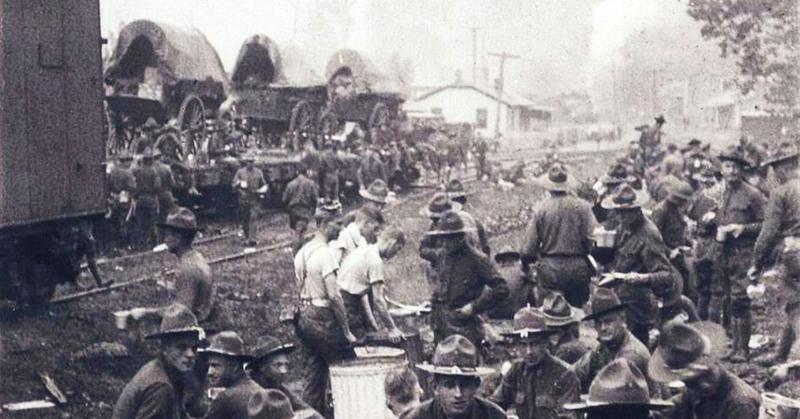

By World War I, tear gas was a mainstay with the U.S. military. Basically, if trench warfare were a video game, tear gas was constantly equipped. The gas was used to get soldiers out of their trenches through "non-lethal" force to give their enemies a clear (very lethal) shot at them. When American troops returned home from the front, they asked to keep their chemical weapons, specifically for use in crowd control. In 1921, an article in Gas Age Record profiling Amos Fries, chief of the U.S. Army's Chemical Warfare Service, explained that using noxious gas for crowd control was a step into a bright, crime-free future because it causes "such a diminution of violent social disorders and savage uprising as to amount to their disappearance."

Police started using tear gas regularly in the 1920s for riot control for a few reasons: They didn't have to use live ammunition, the gas dispersed without a trace within a day, and it didn't leave signs of a physical harm. In 1921, police had their first big tear gas test when they brought down a labor uprising in Logan County, West Virginia. For five days in August and September, 10,000 armed coal miners took on 3,000 officers and strikebreakers over their desire to unionize and be paid actual money rather than company currency. The miners had numbers on their side, but the police had tear gas, pipe bombs, and machine guns. The latter almost always beats the former.

The Golden Age Of Tear Gas

After seeing the effects of tear gas on large groups of people, police departments across the United States spent an ungodly amount of money on the weapon. The big winner in this rush to purchase harmful gas was the Lake Erie Chemical Company, founded by World War I veteran Lieutenant Colonel Byron "Biff" Goss. Sales agents became the ambulance chasers of the weapons industry, following headlines about labor disputes and visiting high-crime areas to convince local police forces that they needed to pick up as much tear gas as possible.

A Senate subcommittee found that between 1933 and 1937, more than $1.25 million (that's around $22,250,989 today) of "tear and sickening gas" was purchased in the States in preparation for strikes. Before America entered World War II, hundreds of police forces were outfitted with tear gas to use against civilians with no need for approval from the U.S. military.

Too Dangerous For War

In 1993, the Chemical Weapons Convention banned any kind of riot control agent from use in warfare, but its use on civilians is an ongoing issue. Proponents argue that if law enforcement isn't allowed to use these supposedly less severe chemical weapons as a form of riot control, they'll be forced to resort to more lethal options. Opponents counter that tear gas totally kills people, and even when it doesn't, it incites panic and leads to trampling. Additionally, they warn, its long term effects are still being studied. According to Sven-Eric Jordt, an anesthesiologist at Duke University, the use of tear gas only exacerbates the situation:

[Chemical agents] are actually dispersed by burning and deposit on the skin or clothing and can persist for a while. They chemically react with biomolecules and proteins on the human body ... I think [tear gases] causes grief, confusion, and increased aggression. And [tear gas cannisters] are obviously not as safe as we think.

Minimizing The Effects of Tear Gas

You may not be the kind of person who attends protests or political demonstrations, but that doesn't mean you'll never face down the sad smoke. A Jethro Tull concert at Red Rocks was hit with the nasty stuff in 1971, as were students celebrating a win by Ohio State in 2015, and it's used with increasing regularity at any kind of political gathering. So how do you protect yourself from being taken out by tear gas?

The best way to keep yourself safe from tear gas is to wear a gas mask, although those can be expensive if you're just picking one up for a protest. A cheap and effective way to buy yourself some time in a riot situation is to prepare a bandanna by soaking it in lemon juice or apple cider vinegar and keeping in a plastic bag in your pocket until you need it. The acidified cloth will help you breathe for a few minutes while you get to safety. You can also wear chemical safety goggles (you know, from chem class) to protect your eyes; the tighter, the better. As a last resort, you can protect your eyes by pulling your shirt up over your face, although it will only take a few minutes of absorption time for this method to become useless. If you wear contacts, you should switch to glasses; anything that's physically in your eyes is going to blind you and slow you down.

The CDC recommends getting to the highest possible ground in order to avoid the dense gas. If the tear gas has been fired inside, get out of the building. Once you're no longer at risk from facing more tear gas, wash your eyes with sterile saline or cold water. Hot water will only open your pores, so don't hop in a bath, no matter how much you desperately need some bubbly relaxation.