The Story Behind the Miranda Rights

By | January 4, 2019

"You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to speak to an attorney and to have an attorney present during any questioning. If you cannot afford a lawyer, one will be provided for you at government expense."

Most people have heard some version of this phrase, even if it was just on one of the many procedural dramas on television, though some may have more hands-on experience with it. Some of those people will recognize this phrase as the “Miranda Rights” which police officers must “read” to suspects before being allowed to interrogate them. What most people don’t know is that the person to thank for this requirement was a career criminal and convicted rapist.

Ernesto Arturo Miranda was born on March 9, 1941, in Mesa, Arizona. He had problems with authority at an early age, often at odds with his father and stepmother. His problems with the law began in eighth grade and in ninth grade, he was convicted of burglary and had to spend a year in the Arizona State Industrial School for Boys. In 1956, only a month after being released from reform school, he broke the law again and had to return.

After being released a second time, he moved to Los Angeles where he was arrested, but not convicted, for armed robbery and sexual offenses, and subsequently extradited to Arizona. Over the following months, Miranda did time in Texas, Ohio, and California for various charges. Eventually, he managed to somewhat get his act together and spent several years out of jail. He worked several jobs before being hired to work the night loading dock for the Phoenix produce company.

On March 13, 1963, Miranda was brought in for questioning after his vehicle and license plate were identified by the brother of Lois Ann Jameson, a seventeen-year-old victim of kidnapping and rape. The truck and plates matched the description which the victim had given to her brother. Phoenix police officers Carroll Cooley and Wilfred Young were able to use this information to track down Miranda, who voluntarily came down to the station to participate in a lineup. He had not officially been arrested at this time. While it is unclear whether Miranda was positively identified during the lineup, the officers led him to believe that he was. After hours of interrogation, during which Miranda was never informed of his rights, the officers were able to get a confession out of him.

He was then taken to meet the victim for voice identification. While in her presence, the officers asked Miranda if she was the victim and he responded by saying “That’s the girl.” Miranda’s voice was identified by the victim. He was then asked to sign a written confession which stated that he had not been coerced and that he had full knowledge of his legal rights; however, he had at no time been informed of what those rights were. Miranda stood trial in mid-June of 1963 before Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Yale McFate. The attorney assigned to represent him, seventy-three-year-old Alvin Moore, attempted to have the confession declared inadmissible, but was overruled. As a result, Miranda was convicted of kidnapping and rape. He was sentenced to thirty years in prison. His attorney appealed to the Arizona Supreme Court but was unable to have the conviction overturned.

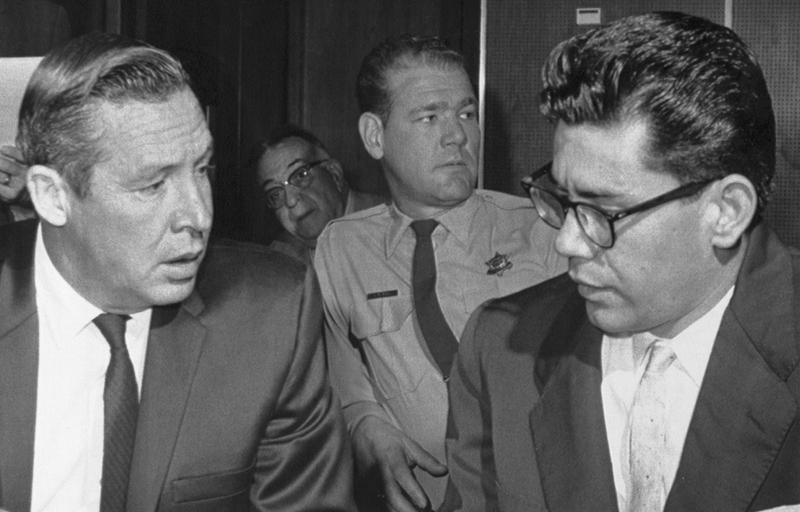

In June of 1965, Miranda appealed to the United States Supreme Court. He was represented pro bono by John J. Flynn and John P. Frank, along with their associates Paul G. Ulrich and Robert A. Jensen, of the Phoenix law firm Lewis & Roca. The attorneys drafted a 2,500-word petition claiming that Miranda’s Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights had been violated, claiming that he had been emotionally disturbed at the time of his arrest and that, due to his limited education, was unaware of his rights to not incriminate himself and to have an attorney present during questioning. In November of 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear his case along with three other cases with similar circumstances.