When We Switched From Horses To Cars: How Did We Stop Riding Horseback Everywhere?

By | December 2, 2020

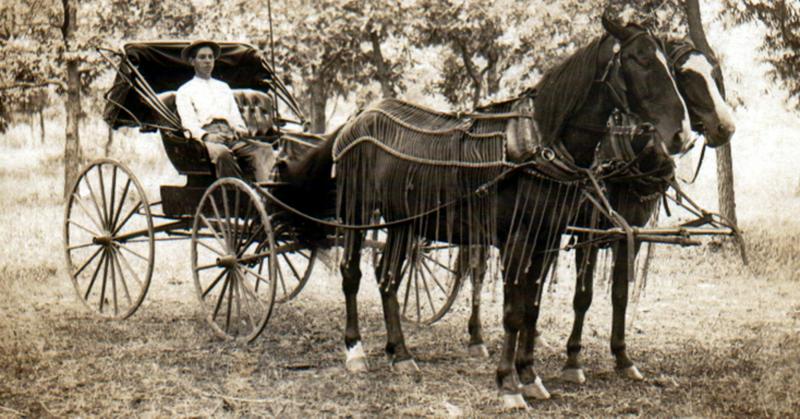

We may look back at the horse-and-buggy days as a simpler, quaint, and romantic time when life moved at a slower pace and people formed strong bonds with their horses, but the realities of life during this time were far less picturesque. Specifically, there was poop everywhere. In fact, horses caused such sanitation issues in large cities that urban planners were desperate for a solution. Fortunately, the invention of the automobile came at just the right time, and we switched from horses to cars.

Horse Poop: A Serious Problem

In the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution meant that more goods were being produced and distributed, which in turn increased the demand for horses to haul goods and people. In the United States alone, horses in urban areas outnumbered people three to one by the 1890s. That translated to a lot of manure, the disposal of which became a growing problem—literally. Any empty lot became a dumping ground for horse manure, and the heaps grew taller than four-story buildings.

It was not only an unpleasant sight (and smell) but a serious health concern. The manure attracted flies by the millions, and those insects carried diseases. Rotting manure and horse urine seeped into the groundwater, contaminating wells and municipal water supplies. Infant mortality and other deaths spiked due to typhoid from contaminated water, but the winters may have been the worst. All that dung dried out and turned to dust in the cold, dry air, which was then breathed in by city dwellers.

Dead Horses

Avalanches of poop weren't the only problem urban horses posed, at least not directly. Horses in those days, especially those living in urban areas, did not have long life spans, and wading through oceans of their own poop all day wasn't very good for them, either. A lot of them dropped dead right in the streets, and moving so much actual dead weight was no small undertaking. As a result, dead or dying horses that collapsed in the streets were merely abandoned and left to rot until they decomposed enough that they could be easily dismembered and remove in pieces. The corpses were often tossed into the giant manure piles, and all in all, it was a horrific, stinky, and unsanitary issue.

The problem of urban horses and their excessive waste was not a new one in the 1890s. In fact, it had been a scourge of cities since antiquity. Julius Caesar even took the drastic step of banning horses and horse-drawn carts from the streets of Rome between dawn and dusk in an attempt to reduce the waste in the streets and its accompanying gag-inducing effects. That wasn't a feasible solution in the Industrial era, though, so Caesar proved to be no help to urban leaders looking for answers.

Band-Aid Solutions

At the rate it was going, the streets of London were projected to be totally buried beneath nine feet of horse manure within 50 years, so in 1898, urban planners held an international planning conference in New York City. City managers from across the globe met to discuss possible solutions to the problem of equine waste, but just three days into the 10-day conference, the delegates threw their hands up in frustration and despair. They declared that simply managing the manure as best they could was the best—and only—course of action.

Attempts by various cities to do so ended with mixed results. Some hired "crossing sweepers" to clear a path across streets so pedestrians could cross without getting stuck in the muck, while others experimented with public transportation, though not as we know it today. The 19th-century version of the subway system consisted of two-horse teams that pulled carriages of 20 or more passengers, which city officials hoped would reduce the total number of horses on the streets.

From Manure To Motors

New York City, meanwhile, hired engineer George E. Waring, Jr. to tackle the issue of manure management in the city. Waring had just finished planning and overseeing the construction of Central Park, and he was eager to continue beautifying New York City. He started by requesting to the city's lawmakers a series of new laws, like requiring horse owners to keep their animals in stables overnight instead of leaving them in the streets. He also hired crews to collect and bag up horse manure to sell as fertilizer, which would have been a terrific idea if the supply hadn't greatly exceeded the demand, and haul the rest outside the city for dumping. Although Waring's efforts were ambitious, they made just a small dent in the problem.

Around the turn of the century, however, motor vehicles (colloquially called "horseless carriages") began growing in popularity. City dwellers quickly realized that owning a car was actually cheaper and less demanding than owning horses, and as an added bonus, automobiles did not leave piles of poo behind everywhere they went. Automobile manufacturers were quick to point out to customers all the benefits of going horseless, and by the early 1910s, there were more cars in New York City than horses, much to the delight of city officials. The city even ended its horse-drawn public transportation services in favor of motorized ones as its residents switched from horses to cars. The great mounds of horse manure slowly disappeared from the city, and the streets, once clean and excrement-free, were paved to make travel easier for car owners.

Cars were not without their drawbacks. Pollution from the internal combustion engines and the exhaust damaged the air quality in cities like London and New York, but it was still preferable to the mess and smell of horses. Although automobile inventors and manufacturers certainly did not create their motorized vehicles to solve the horse manure problem in the world's cities, it was a happy side effect of modernization.